Author: Nanuli Tskhvediani

Many years ago, the esteemed Georgian poet, publicist, and public figure Akaki Tsereteli drew a comparison between the quadrangular shape of Kutaisi Boulevard and Imeretian Khachapuri (a Georgian pastry) due to its shape. Furthermore, because of the constant socio-political passions and heated debates that regularly unfolded in “Bagiskide” (translated as “The Edge of the Garden”), the boulevard was affectionately nicknamed “Parliament of Kutaisi,” a name that has endured to this day.

Many prominent figures described The boulevard using harsh epithets; for instance, George Tsereteli likened it to the Roman Forum. However, Akaki remains to this day the immortal godfather of the boulevard. His connection with the historical garden of Kutaisi, its essence, and its vibrancy was so profound that, in the 1980s, there was a formal proposal to rename Kutaisi Boulevard as the “Garden of Akaki.”

Today, Kutaisi Boulevard holds a special place among the cultural and historical monuments of Kutaisi. Moreover, it is considered a source of pride for the second capital of Georgia, a pride founded on a long, deep, and fascinating history.

From Daredzhan’s Garden to ‘Gulvardi’ (‘Rose of the Heart)

Let’s start with the fact that Kutaisi residential houses, covered in greenery, have had their own gardens since time immemorial, serving both economic and aesthetic purposes for their owners. Among the most wonderful was the garden of Daredzhan, daughter of King Solomon the First. Confiscated by the empire in 1820, it was transferred to the treasury and declared a public park the following year, with surrounding empty state lands added. This marked the first European-type park in Georgia and Transcaucasia, blending Eastern culture with decorative plants, fruit trees, a vineyard, and even a kitchen garden.

This garden, naturally situated in the center of Kutaisi, has retained its purpose as the construction of the future boulevard began. The site of today’s historical boulevard was, in the 18th century and earlier, an arena bordered by variegated plane trees, as described by the esteemed Georgian historian and geographer Vakhushti Batonishvili.

The first outlines of the future garden were drawn on the site of this old arena during the tenure of the Imeretian governor Gorchakov (1820-1825). According to historian Noah Balanchivadze, “the foundation of the Kutaisi boulevard was planted with plane trees by V. Bubukov (1825-1828). This assertion is supported by reports from P. Glinesarov in 1848 and K. Borozdin in 1850. Greater credibility is given to Peter Glinesarov, as he was serving as the vice-governor of Kutaisi at that time.”

This revelation establishes Kutaisi Boulevard’s age at at least 175 years!

“The identity of the specialist boulevard-builder, along with the plan and direct involvement in its creation, remains unknown,” Noah Balanchivadze notes, “though it is speculated to have been a French gardener. This is suggested by the garden’s original French name and the design’s French horticultural influences. This speculation is bolstered by the known involvement of French specialists in our city’s ‘green construction’ during that era. For reasons unknown, the new park was named ‘boulevard,’ a term denoting a wide city street alley, distinguishing it sharply from the older city garden, which hosted diverse plantations, including a vineyard and a vegetable garden. The Georgian variant of ‘Bulvar’ – ‘Gulvardi’ translated as( Rose of the Hart), emerged soon after, applying an Imeretian twist to the French term.

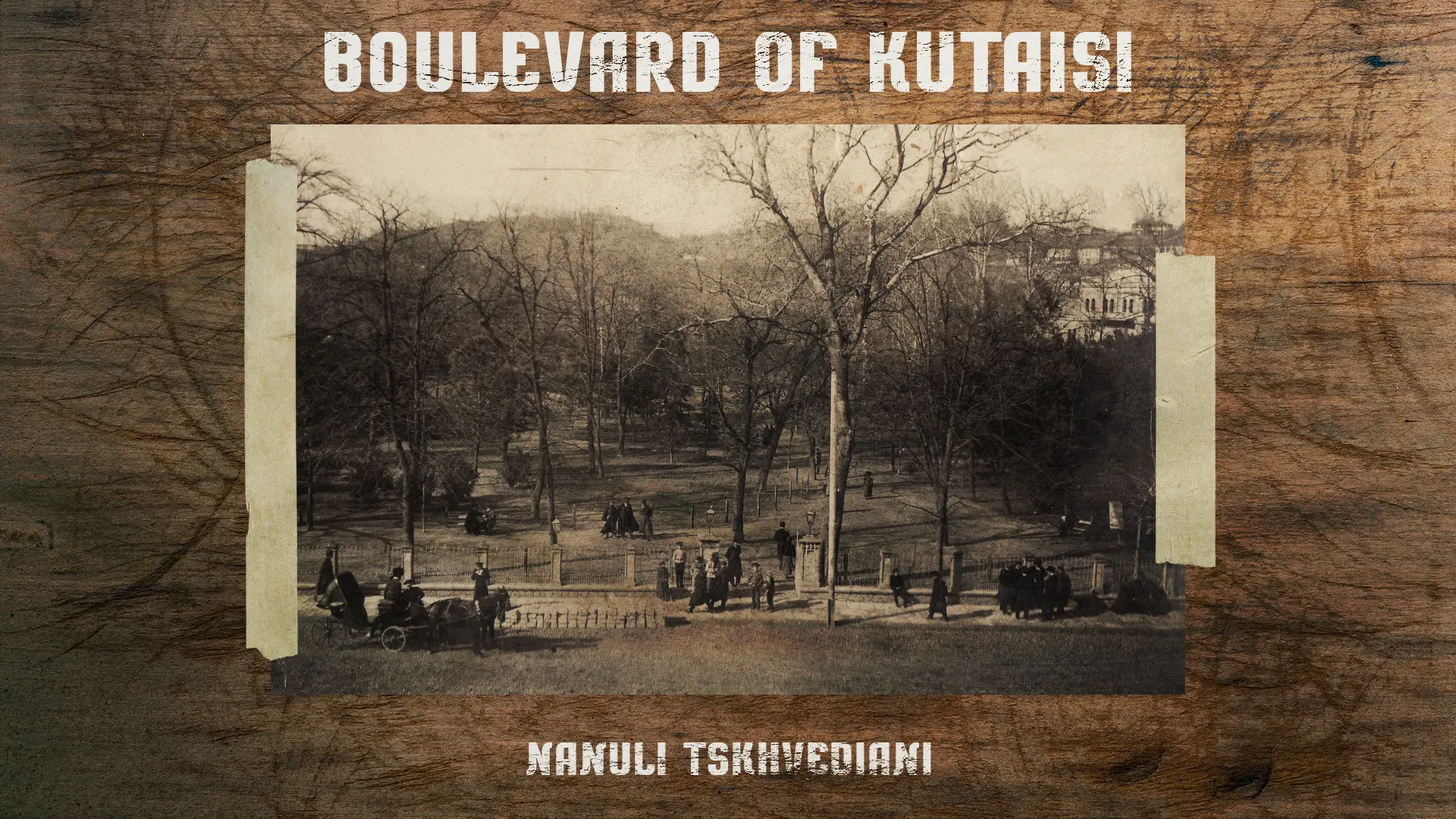

In the 1850s, as a correspondent of the ‘Kavkazi’ newspaper reported, the Kutaisi boulevard was shaped like a wide square, enclosed by a red wooden fence on all sides. An alley ran parallel to the fence from the inside, intersected by two more alleys in the form of a cross, with a dance floor at their intersection. Flowers and tall trees lined the alleys, their leafy branches providing delightful shade, while long wooden and stone benches offered rest. The boulevard was predominantly covered with green lawns. On Sundays, music filled the air, attracting Georgians in vibrant attire to sit on the grass, enjoying the harmonious blend of music of zurna and nature. On weekdays, the garden saw fewer visitors. By the 1870s, it had become a place for daily gatherings.

By then, mineral water from Kibula was brought in, and non-alcoholic beverages were sold at a kiosk. M. Vladykin notes that small, beautiful bridges crossed over ponds, offering a charming view to pedestrians. The wooden fence, so-called “ Reshotka,” erected in 1878 by city initiative, soon aged. Funds for replacing the iron grate embedded in stone were obtained from the taxes paid by Constantine, Prince of Oldenburg, on his purchased plot on Balakhvni Street after he moved to Kutaisi. The construction of this fence stretched out and was completed by 1891, with paving laid outside the garden. A poignant joke by Akakia likened the fence’s pillars to cemetery monuments, noting “their number matched that of voting officials in the city.” This strict iron fence, disfavored by Georgia’s beloved poet, was dismantled only in the 1970s, returning the area to its natural boundaries.

Buildings and Monuments

The boulevard has seen numerous transformations throughout its existence, often reshaped by the demands of authority. This area witnessed the rise and fall of various structures, reflecting the changing times and needs of its people.

One notable structure was the pavilion constructed in 1891 to honor a visit from Emperor Alexander III. Funded by contributions from the entire population of Imereti, this stone-brick edifice was plastered on the outside. It boasted an interior supported by seven columns, topped with intricately carved wooden columns and railings. Initially serving as a theater, it was here that the renowned actor and director Kote Meskhi began preparations for future performances. Tragically, on October 12, 1894, a fire erupted following a general rehearsal, rapidly consuming the wooden components of the building. The pavilion was destroyed within 15-20 minutes, and the theater’s assets were lost to the flames. The 1940s saw the establishment of a summer theater on the same site, though it too would only last two decades before its abrupt demolition.

In 1948, an entrance colonnade was erected on the eastern side of the boulevard, adding to its architectural features. Significant monuments also grace this boulevard, marking it as a cultural memory and honor site. In 1941, a monument to the esteemed poet Akaki Tsereteli was unveiled, sculpted by Valerian Topuridze, a People’s Artist of Georgia, commemorating the poet’s 100th anniversary. The 100th anniversary of the birth of Zakaria Paliashvili in 1970 saw the erection of a monument to this celebrated composer, the work of sculptor Levan Mkheidze. Another poignant addition in 2006 was the “Suliko” monumental composition, honoring the legendary Ishkhneli sisters, crafted by the honored artist of Georgia, Georgiy (Gogilo) Nikoladze, with architecture by Givi Todadze. Todadze also designed the original fountain at the boulevard’s center.

A testament to changing political landscapes, a monument to V. Lenin once dominated the boulevard from 1950 to 1990, standing tall on a high pedestal. It was removed following the advent of the national government. In March 2017, a touching tribute to the victims of April 9, a bronze monument crafted by Honored Artist of Georgia Rezo Ramishvili, was relocated to the boulevard from Tsisperkantseli Street.

Recently, the boulevard has embraced modernity by introducing designer tables and decorative trash cans. Enhancements include two parallel basins for fountains and a circular flowerbed, infusing the space with beauty and functionality.

Presently, the local government has embarked on a comprehensive rehabilitation project to align the boulevard with contemporary standards, ensuring its decorum and utility. The entire area is now encircled by a green construction fence, signaling the commencement of activities by the winning tender company, promising a new chapter in the boulevard’s storied history.

The Magnificent Boulevard Society of Kutaisi

The garden, which the empire’s planners initially intended to be merely a harmless place for rest and entertainment, unexpectedly expanded its purpose from the moment of its creation and became the center of public activity in Kutaisi and the entire province—an arena for the dissemination of progressive views. Initially, it was frequented by the aristocracy, who were primarily interested in entertainment and government officials. According to the writer George Tsereteli, “Kutaisi Boulevard… had the same importance for the city as coffee shops and clubs had in Paris… there was always only laughter here and fun.” The epochal changes of the 1860s were acutely reflected here, especially since the 1870s, when self-government was introduced and a national bank was opened. These institutions were elective in nature, and especially during the elections of the bank’s head, the nobility of the entire province gathered in Kutaisi on its boulevard, making it a public property.

It was here, on the boulevard, which Akakiy dubbed the “Kutaisi parliament,” that good and bad candidates were chosen, directions were formed, arguments made, and various election strategies were developed. Another witty comparison by Akakiy referred to the boulevard during election days as “trick square.”

According to the public and political figure Samson Pirtskhalava, “The city garden, the so-called ‘boulevard,’ played a significant role in the life of Kutaisi. If you wanted to see someone, you would meet here; here, there was buying and selling, collateral, hiring, lending money, matchmaking. There were debates, and here, there was an exchange; it was like a showcase of people, beauty, stateliness, clothes… The boulevard was always full of people, day and night. Military music was played on Sundays and twice a week, further attracting the walkers. Nowhere could you meet such pure Georgian, beautiful people as the representatives of our aristocracy at that time, who were distinguished by grace and elegance: Tsereteli, Tsulukidze, Mikeladze, Dadiani, Pagava, Gurieli – women and men.”

And yet, the Boulevard had its chosen ones. Along with Akaki, these were the most famous personalities of different times: Kirile Lortkipanidze, a prominent representative of the great generation of Tergdaleuli, dubbed by Kutaisi society as the “white-bearded Aristide,” Solomon Leonidze, the Gogoberidze brothers, Rafiel Eristavi, Georgiy Tsereteli, Niko Nikoladze, David Heltuplishvili, Georgiy Zdanovichi-Maiashvili, Moses Kikodze, Dmitry Nazarishvili, Pavle Tumanishvili, Data Nizharadze, Mamia Guriel, George Sharvashidze, Konstantin (Kotsia) Eristavi, Anton Purtseladze, Luka Asatiani, Elijah Chikovani, Isak and Ivane Puradashvili, Solomon Micheladze, Dmitry Bakradze, David Bakradze, Erothy Sidamonov-Eristavi, Gerasime Kalandarashvili, Sergey Meskhi, Petre Nakashidze, the Eristavi family, David Kldiashvili, Ivane Zurabishvili, and many others.

Echoes from the Old Boulevard

The Old Boulevard remembers those young people from Kutaisi who passionately read Melkizedek Abesadze’s book, published in the “Gubernski Printing House” – “Love Poems from Guys to Young Girls.” It also remembers the old Olympian, “The Uncrowned King of Georgia,” Akaki Tsereteli, sitting in his worn-out favorite spot in a cozy corner opposite the “Soboro,” who was never left alone by those around him. The first shots of Akaki’s famous trip to Racha-Lechkhumi were filmed on the boulevard by Vasily Amashukeli from Kutaisi, the first Georgian cinematographer, and the film concluded with the poet and his followers returning to the boulevard.

The boulevard also recalls the “intoxication with playing lotto,” as Akaki put it, of aristocratic ladies who, under the light of night lamps, were deep into their gambling games even at 10-11 p.m., quickly eating “varenje”(jam) for supper, eager to return to their beloved pastime. It remembers the “Georgian Library” publication, produced by women from Kutaisi under the editorship of Ekaterina Lortkifanidze, which supplied society with translations of foreign progressive works into Georgian.

It bears the memory of the unparalleled recitation of the noblest aristocrat, poet of tragic fate – Mamiya Gurieli, and the stunning beauty of Kutaisi’s women and men who gathered to see the living drawings of Mihai Zychi from “The Knight in the Panther’s Skin.”

The great euphoria of 1905-1907, the revolutionary barricades, and the story of General Alikhanov-Avarsky’s wounding are all etched in its memory. For many years, the boulevard was filled with the rustling of pages from books printed in the Peradze, Gamrekeli, Tsulukidze, Gambashidze, Kiladze, and Kheladze printing houses, and dozens of new newspapers published in Kutaisi, not to mention the specially ordered “Iveria” and “Droeba.”

Debates and literary themes that started in the literary salons of David Mikeladze-Mevele, Elena Kipiani (daughter of Dmitry Kipiani), and the sisters of Niko Nikoladze often continued here. The Kutaisi community was enchanted by the knowledge and extraordinary intellect of the young scientist and writer Doctor of Philosophy Grigol Robakidze, who was educated at the universities of Tartu and Leipzig. His lecture on Friedrich Nietzsche made even Akaki himself say, “I saw what I had dreamed of all my life: a Georgian intellectual, thinking independently, not merely echoing like a gramophone.”

The boulevard elite was the first to sense the approach of a new pinnacle of Georgian poetry – Galaktion, and alongside the great Akaki, gave his poems the same high esteem in the periodical press. In 1914, the new king of Georgian poetry made his way onto the boulevard with his first book, printed at the Tutku Gvaramia printing house in Kutaisi.

In 1915-1916, the conservative “Edge of the Garden” keenly discussed the product of the symbolist school “Tsisperkancelebi” (The Blue Horns) with its strange name – “Blue Branches,” formed by “some” young poets – Tite Tabidze, Pavle Iashvili, Nikoloz Nadiradze, Valerian Gaprindashvili, Alexander (Sandro) Tsirekidze, and their friends. Surprisingly, such a skilled reader and evaluator as the critic Kita Abashidze supported “these impudent children.”

Titian Tabidze, one of the founders of this school and the author of two manifestos, would later say, “Kutaisi appeared to us then as the dead Bruges of Rodenbach… a city of impoverished small landowners who had already sold their estates and long ago become a city of people trained in cunning, idle idlers – this provoked in us a bohemian-oppositional attitude towards mediocrity and led us against the ‘public taste.’”

Indeed, later, the Boulevard also came to appreciate the novel expressions of Titian, Paolo, Colau, and their rebellious friends within Georgian poetry. In the boulevard’s shade, audiences from two major nearby cinemas – “Mon-Plas” and “Radium” – discussed new films, including documentaries by Vasil Amashukeli. Meanwhile, the “Edge of the Garden” theater, from its early years and with significantly sharper emotions, for the first time selected a repertoire featuring Kote Meskhi and his grand theater, showcasing roles by Mako Safarova-Abashidze, Nato Gabunia-Tsagareli, Nino Chkheidze, Elizabeth Cherkezishvili, Tasso Abashidze, Vaso Abashidze, and Kote Kipiani. Then, it proudly recounted how Lado Meskhishvili “faced down” the renowned Adelgeim brothers, who had toured Kutaisi by strategically scheduling his performances (“Rui Blaise” and “Hamlet”) in between theirs. Writer and actress Mariam Garikuli described how on the rejuvenated stage, Lado, adorned with a hat featuring ostrich feathers and a white tweed tunic, shone like the sun, captivating the audience to the extent that actress Liza Gvetadze was spellbound, her expression changing multiple times before she, crossing herself, hesitantly stepped onto the stage. The people of Kutaisi took pride in that neither Mamont Talsky, Orlenyev, nor any other great actors who visited at various times could lure the audience away from Lado.

Much later, between 1928-1930, another genius, Kote Marjanishvili, captivated Kutaisi and its theatrical “Edge of the Garden” with his debut performance. Poet Lili Nutsubidze shared stories heard from the older generations of Kutaisi, recounting how to the southwest of the boulevard, under one of the plane trees, members of Marjanishvili’s group would gather, and here, amidst Ushangi, Veriko, and other distinguished figures, the great Kote was often present. Regrettably, this historic plane tree was sacrificed years ago to facilitate the expansion and renovation of the opera house and to establish a “public auditorium” for television broadcasts…

The boulevard, every nook and cranny of it, primarily served as a stage for the finest performers of city and folk songs. In the last century’s final decades, the illustrious princes and their friends- Bondo and Pipinia Mikeladze, Kokinia Dgebuadze, Niko Pagava, Kotatia Mumladze, Mina Bolkvadze, Daniela Uria, and others, relinquished supremacy to no one. Legend has it that the Kutaisi community threw a grand banquet in honor of Vano Sarajishvili and Sandro Inashvili’s tour visit, where the Imeretian princes astonished the celebrated singers with a magnificent rendition of “Tseduri Polycronion” at the table. It was said that Daniela Uria led the song, elevating her voice to the heavens and sustaining it until the moved princes laid thirty gold rubles on the table, which she had requested by raising three fingers.

Beautiful songs performed by gymnasium students were often heard on the boulevard, with groups competing against each other. Among them, the brothers Dmitry and Bidzina Mchedlidze were unrivaled. The youth would stop singing when they saw Ioseb Otskheli, who had left the gymnasium and was walking home along the boulevard. The old director made them feel embarrassed, and they hid behind the trees.

“Edge of the Garden” song repertoire was often based on real stories. For instance, a new “song” emerged in the Kutaisi Argan of the 1910s, passionately sung by the then youth of Imereti: “I’m leaving Kutaisi, Goodbye, Alice!” According to Revaz Gabashvili, the son of the political and public figure Ekaterina Gabashvili, this Alice was a beautiful cleaner working in a Kutaisi hotel, whom a young Imeretian prince, having arrived from St. Petersburg for a vacation, fell in love with and persuaded to marry him. Unfortunately, besides carrying water buckets from floor to floor, this beauty had other “duties” at the hotel, and the unfortunate groom only discovered this when he caught her in a very compromising position with one of her admirers. Before fleeing the hotel, heartbroken, the prince left the aforementioned exclamation poem on a piece of paper for the woman, which quickly spread throughout Kutaisi and was even turned into a song.

However, it wasn’t only such kitsch that captured the heart of Kutaisi Boulevard. Classical and folk masterpieces were also beautifully performed here, and the art of both local and visiting talents was highly esteemed. On the old boulevard, the sweet-voiced girls of Ishkhneli were spoken of with great admiration, especially when their school director nearly expelled them for participating in a nighttime concert.

Kolya Kvariani, a boy who unobtrusively appeared in the “Kutaisi Circus,” became a sensation after defeating the famous Russian wrestler known as “Black Mask.”

The rivalry between Kolya Kvariani and Georgik Iashvili, who possess extraordinary strength, is also well-remembered here. Iashvili, known for his iron fist, would bend an iron fence with his fingers whenever a beautiful lady passed by, while the city’s boxing king would straighten it and bend it back again (according to another version, this happened not when he saw a beautiful woman, but whenever he was leaving or entering Kutaisi).

Another noteworthy chapter in the boulevard’s history was the “Daisy” festival, which, starting in the 1910s, became a tradition for aiding tuberculosis patients. Beauties from Kutaisi (including the exceptionally beautiful Sasha Chikovani), followed by high school girls and boys with baskets full of daisies, would attach the daisies they sold for charity onto men’s lapels in tailcoats. A special committee used the money collected over three days to assist the sick.

Boulevard also had its favorite themes – high-profile romantic stories. For example, there were rumors that the beauty of the imperial court, the brilliant Prince Ucha Dadian, loved the beautiful wife of Alexander Dadeshkelyan, and perhaps it was he who contributed to the murder of a father of a large family on the boulevard… The second married beauty caught the eye of Konstantin of Oldenburg himself, who, with money or by force, compelled her husband, Tariel Dadiana, to cede his wife to him so he could marry her and make her the beautiful Countess of Zarnicaud. In Kutaisi, they sang to the accompaniment of bowed guitars for a long time: “Dadiani gave the laughing Agrafina to the prince…” However, according to another version, Dadian did not give up his young wife in exchange for money.

And finally – let’s remember the world-famous Kutaisi humor, sloppy puns – “Okhunjoba,” which have always been characteristic of the Boulevard and were created by such great masters as Sergia Eristavi or Pipinia Mikeladze! Following in their footsteps, generations have enriched the folklore treasures.

If not on the boulevard, then where else would the folklorist and public figure Pipinia Mikeladze could utter this famous phrase: “Kutaisi should be declared a natural reserve, where only noble, well-mannered, and patriotic Georgians would have the right to enter without a pass.” Ilya Chavchavadze, who came to Kutaisi for the funeral of Bishop Gabriel, invited him to Saguramo for his birthday, where young Pipinia so skillfully managed a table for two thousand people as a toastmaster. It turns out that the Imeretians who came with him, dressed in beautiful white “chokhas”( traditional Georgian coats), stood out with their charming appearance, songs, and speeches, captivating the audience.

Living Plant Museum

The venerable age of the plant species present today on Kutaisi Boulevard suggests that the dendroflora remains almost in the same state it was initially planted in. This is supported by the fact that there are only a few young plants.

Researcher Boris Tvalodze, who first described the dendrology of the boulevard, reports that the vegetation comprises 30 botanical families, with the number of species reaching 51. Most of them are exotic specimens from different corners of the world, making the garden unique and akin to a living museum of plants. Another distinctive feature is that most species here are represented by only one specimen, and a single species’ average number of plants does not exceed five.

Most plants are old, necessitating special attention and renewal of the same species in the garden. This is particularly important for introduced species. Notably, some plant species do not self-renew, primarily because the crowded garden located in the city center is very busy. Secondly, the road and paths throughout the garden area are entirely covered with concrete, which worsens the overall condition of the trees. According to the specialist, removing the concrete covering and replacing it with decorative gravel is necessary to create conditions conducive to flora life.

“Here, the merry din of others resounds…”

The historical boulevard has not lost its traditional essence – alongside being a place of rest for the population, it remains a source of public opinion, meaning the ancient “Parliament” of Kutaisi still actively debates socio-political, cultural, socio-economic issues, self-governance problems, and matters of both private and public significance. Witty phrases and sharp contemporary humor are still crafted to this day.

The new “Edge of the Garden” still recalls the “Sataphlian Mindia,” who walked from the boulevard to the museum with a blue cloak draped over his arm – the white-haired Petre Chabukiani, the discoverer of dinosaur tracks and archaeological sites at Tetramitsa; The epitome of human virtues, the handsome Meoba (Otar) Sulaberidze; Sculptor Valiko Mizandari, the great narrator of hunting adventures; The muse and friend of many great artists, the Jewish photographer Ilo (Khakhiashvili), who never left Kutaisi and was always at its heart; Plus many more colorful individuals from Kutaisi, including writers, journalists, actors, musicians, doctors, teachers, athletes, and professionals from other fields, have left an indelible mark in the collective memory.

The beautiful “ideology” of today’s boulevard, the love for one’s hometown along with the moral and patriotic examples set by the older generations, are encapsulated in the “Kutaisian” works of great writers – Rezo Cheishvili and Rezo Gabriadze.

To withstand the desires of some over various eras, to ensure that in the future, no one arbitrarily decides to redevelop the area, establish parking lots, or encroach on the vegetation and monuments, the historical boulevard must be granted the status of a cultural heritage monument.

Let us not forget: the 175-year-old Kutaisi Boulevard is a part of the grand urban culture, a living monument to a proud past!

.