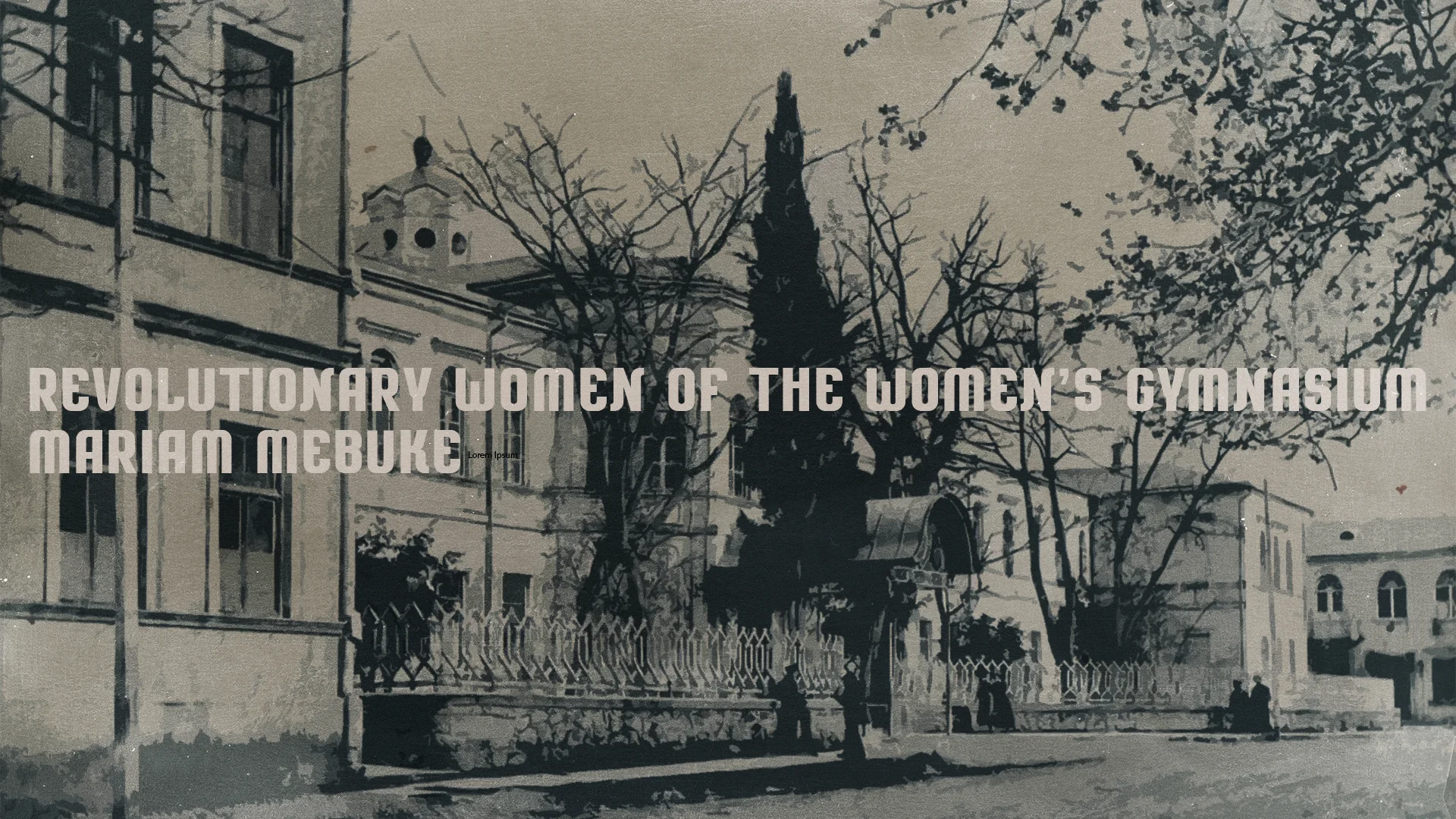

Revolutionary Women of the Women’s Gymnasium

Mariam Mebuke

“I have specific military knowledge, and she has feelings. And feelings are always more intense, more impressive than facts.”

“War does not have a woman’s face.”

— Svetlana Alexievich

When we realize that we have forgotten the past, that our collective memory has deceived us, we see that this state of oblivion often lasts longer than it should.

This seemingly abstract introduction is dedicated to women who shaped history with their lives and even more with their work. Today, I am writing about the revolutionary women of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who had some connection with Kutaisi and who left behind remarkable stories about this city.

Names may fade over time, but stories endure. Since we are discussing the protests of repressed women, a voice that is always heard, it is no coincidence that the “voice of the Georgian woman” begins in Kutaisi, speaking her mind openly.

Minadora Toroshelidze was born in the Kutaisi district and graduated from what is now St. Nino Third Public School. She was a Marxist, a member of the social movement, and a participant in the Founding Assembly. In her diary, she recalls an important event from 1898.

At that time, members of the “Mesame Dasi,” the first social-democratic party in the Caucasus, moved from Tbilisi to Kutaisi, where they began establishing underground circles. This moment in her biography touches on the political events of Kutaisi at the end of the 19th century. Unfortunately, little information remains about these underground activities, but one thing is certain—such movements played a crucial role in the “revitalization” of the city under Tsarist rule.

The activities of these women are fascinating because they lived through countless experiences, often witnessing and influencing the lives of many others. In Minadora Toroshelidze’s memoirs, she recalls meeting Lado Meskhishvili, a key figure in Kutaisi’s cultural scene.

In this memoir, Meskhishvili speaks about the difficulties faced by the Kutaisi theater, which was struggling under the censorship imposed by Russian rule. He also notes that educated women refused to join the theater troupe and asks Minadora to delay her departure for education, encouraging her to become an example for women from noble families. She agrees, and the effort proves successful.

Finding links between Kutaisi, its resistance movements, and the historical context of the time is easy, but gathering information is difficult. The records are scattered, making the overall narrative appear somewhat chaotic. Yet, this can be seen as a metaphor—an allegory of that turbulent period.

Another remarkable woman was Kristine (Chito) Sharashidze, also a graduate of the Kutaisi Women’s Classical Gymnasium. In her diary, she documents the October Revolution, particularly the general strike of October 14-24, which led to the complete isolation of Western Georgia:

“As a result of the ten-day general strike (October 14-24), all of Western Georgia, from Khashuri to Batumi, was cut off. The railway was damaged, the telegraph stopped working. The Likhi Pass tunnel was blocked with broken steam locomotives. Batumi, Guria, Kutaisi, Shorapani, and Samtredia were completely isolated. No one knew what was happening there.”

Another forgotten episode from Kutaisi’s history took place in 1907. Revolutionary prisoners dug a tunnel under the city prison and escaped. The tunnel, constructed by miners from Chiatura, was an impressive engineering feat for its time. This event, well known in Georgian history but often overlooked today, is directly linked to Kristine Sharashidze. She lived on Balakhvani Street and often sheltered the escaped prisoners in her home.

The gendarmerie of the time closely monitored events in the city, especially after the prison break. Kristine recalls a police search of her house. They found nothing—or rather, no one. Aside from personal notes, there was nothing of interest to the authorities. One gendarme, Esadze, secretly slipped her a “black notebook” under the table and whispered, “Destroy it!” It is easy to guess why. If we consider Kristine’s reference to the underground press published on Semyonov Street, which was later visited by Stalin himself, the significance of these notes becomes even clearer.

Semyonov Street was once located where the Kutaisi Botanical Garden now stands, though little information remains about the printing house that operated there. During the same period, the People’s University Society existed in Kutaisi, promoting education and literature despite the difficult political climate.

After the communist regime took power, the woman who had once fought against Tsarist rule became an opponent of the new government and joined the resistance movement. Her indictment states:

“…The investigation established that the accused is an irreconcilable enemy of the existing order and is using every means to overthrow the Soviet regime and restore Menshevik rule. In her testimony, she clearly states that the Soviet order and government in Georgia are a fiction.”

Another revolutionary woman, Ketevan Khutsishvili, wrote in her memoirs that she “belonged to the Georgian Young Marxist Organization.” This was a youth movement founded in 1915 at an illegal meeting in Kutaisi. The city had the conditions necessary for such an organization to emerge, providing a relatively safe environment—though “safe” is a questionable term given the political unrest of the time. Nevertheless, Kutaisi played a key role in the beginnings of this movement.

The article begins with a quote from Svetlana Alexievich’s War Has No Woman’s Face. By remembering these forgotten women, I hoped to show that emotions are more powerful than facts. However, this mission is ultimately impossible—too much history has been lost under Tsarist and later Soviet rule. There is still much more to write about the students of the women’s gymnasium, who bravely stood by their principles and morality. Their story does not end here.

Grigol Abashidze captures the strong emotions of military knowledge and revolutionary struggle in his poem Ode to Freedom:

“The dream of the people, the longing of the shepherds,

Comes, scattering lightning like bullets…

Their coming is like the sunrise, and

All is forgiven to them.” (literary translation)

All of these women carried the spirit of freedom within them.