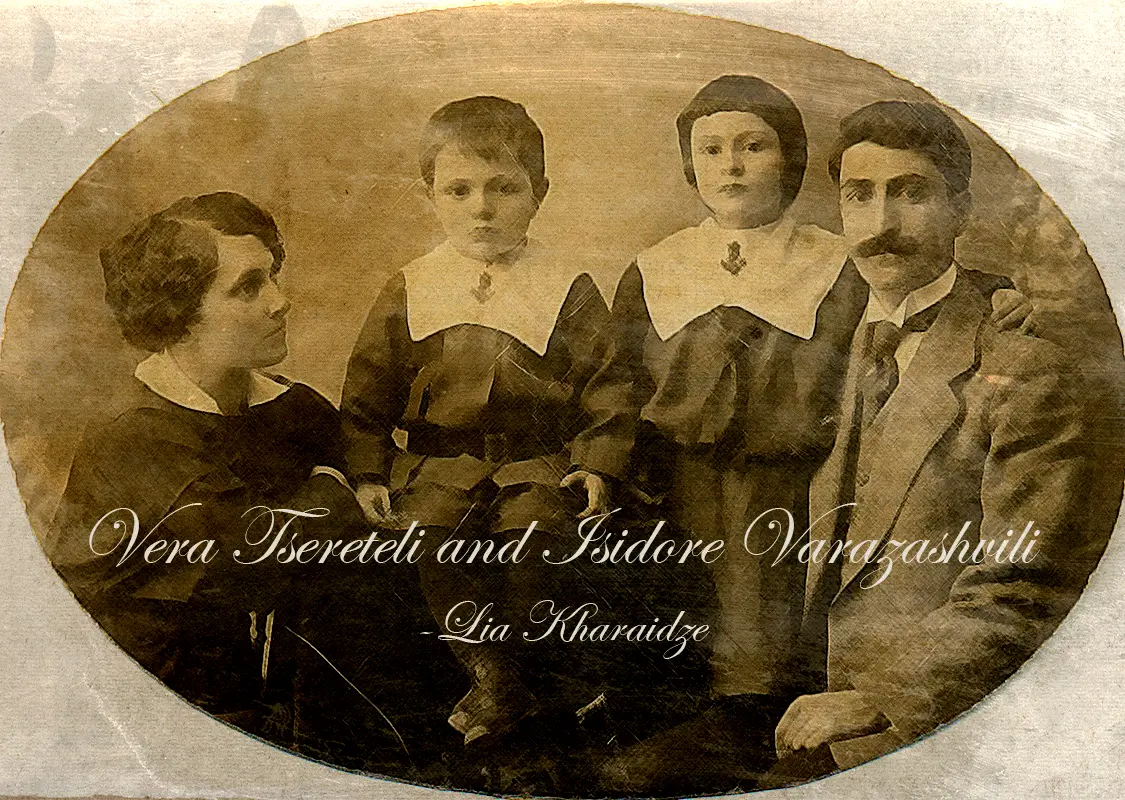

Author: Vera Tsereteli and Isidore Varazashvili

Traveling from Chiatura, bypassing “Davis Namukhlari” (a place below Mukhatgvedi, a rock obstructing the road from Tbilisi to Dzegvi), you will leave behind Sveri fortress and “Kotia Cave,” eventually reaching the village of Tskhrukveti. Here, in the old cemetery beneath the church of St. Marina, a stone entwined in vegetation will surely catch your eye. This crypt belongs to Vera Varazashvili, as the inscription indicates. Isidore Varazashvili constructed this eternal crypt in profound love and sorrow for his beloved wife.

“My life, my Veriko… I live by you and rejoice in the world through you, easily enduring all hardships in the hope that it will be well for you and our children with me. Remember this, my hope.”

Who was Vera Tsereteli, the woman Isidore Varazashvili wrote about with such love and respect? A renowned entrepreneur and philanthropist, he was one of the founders and the first chairman of the “Chemo” joint-stock company. (According to some accounts, he invited Niko Nikoladze to become the first chairman. Unfortunately, the Varazashvili brothers are lesser known to the public, as their families were repressed, and discussing them was considered taboo.)

Vera hailed from the illustrious Tsereteli-Modzgvrishvili clan, which contributed many notable figures to society: Vasily, Mikhako, Alexander, George, and Tina Tsereteli.

Vera was raised in an environment frequented by Akaki Tsereteli, Galaktion Tabidze, Georgiy Zdanevich, Niko Nikoladze, and Kita Abashidze, fostering her active engagement in social causes.

Vera’s love story with Isidore began upon his arrival in Chiatura on business. Isidore’s entrepreneurial pursuits were closely intertwined with his philanthropic efforts. Noteworthy is the charitable work of Isidore Varazashvili and the “Chemo” joint-stock company, including the establishment of the Rustaveli Society in Hamburg and Munich, which significantly supported Georgian students abroad. David Kakabadze, Sergo Kldiashvili, and Konstantint Gamsakhurdia, among others, benefited from this aid for their studies in Europe. A significant contribution was also made to the newly established university, including the procurement of a library and a request from Ivane Javakhishvili to Isidore in Germany to purchase a laboratory for the university. The extensive philanthropic endeavors of the society merit further discussion at another time.

Returning to Vera’s story, Isidore, alongside George Nutsubidze, initiated the Society of Stage Lovers in Chiatura and participated in its theatrical productions. The vibrant and energetic Veriko also became a troupe member. Isidore’s close ties with Vera’s family, especially her brother Alexander, highlighted her undeniable presence and dynamism, inevitably capturing Isidore’s attention.

In 1907, Vera and Isidore married. Vera’s eventful life didn’t cease after her marriage. Her personality is vividly depicted through the memories of her friends, Lida Lezhava and Nina Asambadze: “After the summer holidays in 1912, on September 15, we came to the Tbilisi Women’s Higher Courses building… We were drawn to a beautiful, vibrant Georgian-speaking woman of medium build with her head uncovered… Later, we learned she was from the Tsereteli family in Chiatura. This was a period when Georgian women had less opportunity to attend higher education institutions. Although the women’s courses had been running in the Georgian capital for four years, there were only three to four trainees in the first year, the rest being Russians and Armenians.” The elder Varazashvili family also wasn’t thrilled about the young married woman enrolling in the Tbilisi women’s higher educational courses.

Nonetheless, her husband supported and encouraged her: “My dear, if you don’t delay starting your studies, it will be good,” Isidore, who had evaded the gendarmerie, wrote to his wife. “It will be good if you manage to pass the exam in May. This will significantly ease our joint efforts in the future, my dear; let’s diligently work, and God will assist us.” The extent to which women’s education, particularly for married women, was limited and frowned upon at the start of the last century is evident from the aforementioned friends’ letter: “We invited Vera over, and she joyfully accepted our invitation. That evening, the three of us drank tea and joyfully reveled. Until that day, we knew Vera as a woman from the Tsereteli family, but then we discovered she was Isidore Varazashvili’s wife and the mother of little Soso and Taliko. This revelation astonished us, as Vera didn’t give off the impression of a woman with a husband and children, such was her vivacity and zest for life.” The letters from Vera’s friends clearly reflect the era’s spirit and the young people’s hopes and dreams: “She (Vera) immediately prophesied that the dawn of Georgia’s liberation was near. ‘Girls,’ she told us, ‘I believe that after 100 years of bondage, Georgia will gain its freedom, our long-held dream will come true, and it will all happen before our eyes.’” Sadly, Vera did not live to see the birth of the Republic of Georgia. In 1918, a pandemic swept through Europe, claiming 50 million lives, inevitably reaching Georgia. The ‘Spanish flu,’ as it was dubbed, swiftly spread across the city. The market square in Tbilisi was transformed into a reception area for the sick. Vera instantly became a nursing sister, caring for the ill. The volunteer help was desperately needed as the medical staff was overwhelmed by the influx of patients. Tragically, Vera contracted the Spanish flu and succumbed to it at the young age of 30. As mentioned initially, she was buried in her native village of Tskhrukveti. Isidore could never have imagined burying his beloved wife, comrade, and ally. He constructed a crypt and engraved all his feelings into its carvings.

Following the establishment of the communist regime, the Varazashvili family faced immense tragedy. Isidore was arrested alongside his son-in-law, Alexander Tsereteli, and his daughter, Tamar. Isidore died in exile, likely executed. Soprom, his son, was executed without trial shortly after being captured. Vera and Isidore’s personal letters were passed down to us by Soprom’s daughter, Vera Varazashvili, named after her grandmother. I wish to conclude this narrative with an excerpt from this poignant, affectionate letter.

“My life, Veriko!”

…I implore you to write to me more frequently. You aren’t as isolated from the world as I am. Please share your thoughts and impressions with me. Could you update me on the news in our country? Your dream intrigued me incredibly. Veriko, it doesn’t surprise me that you have such dreams. Everything must resonate profoundly with such a sensitive and tender soul as yours, my dear… May God make your dream a reality. It speaks volumes to me about your and our family’s role in our country’s life. I send countless kisses to the children. I eagerly await your letter. Be healthy, my life, and happiness. Remember me.

Yours, Isiko”