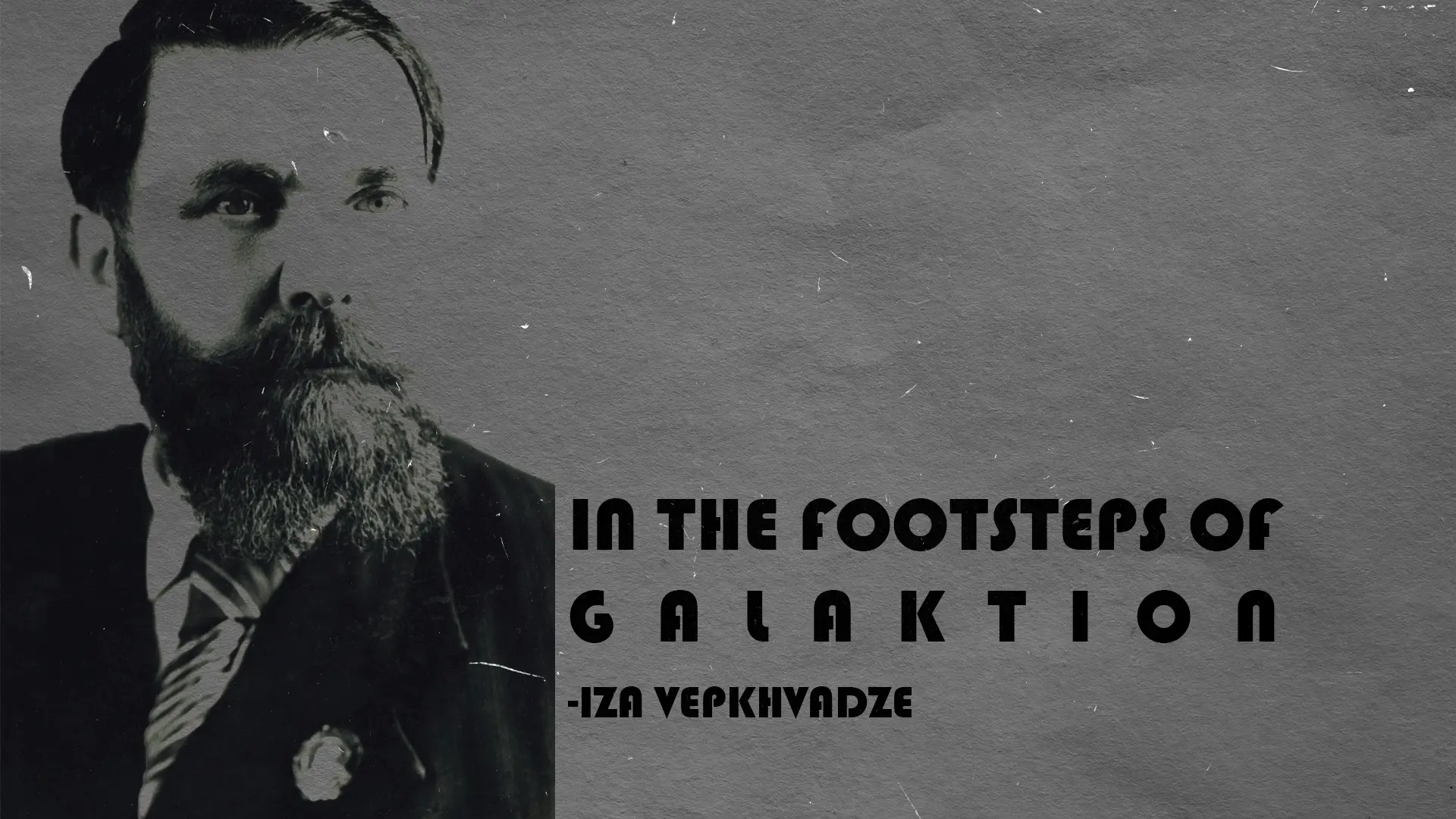

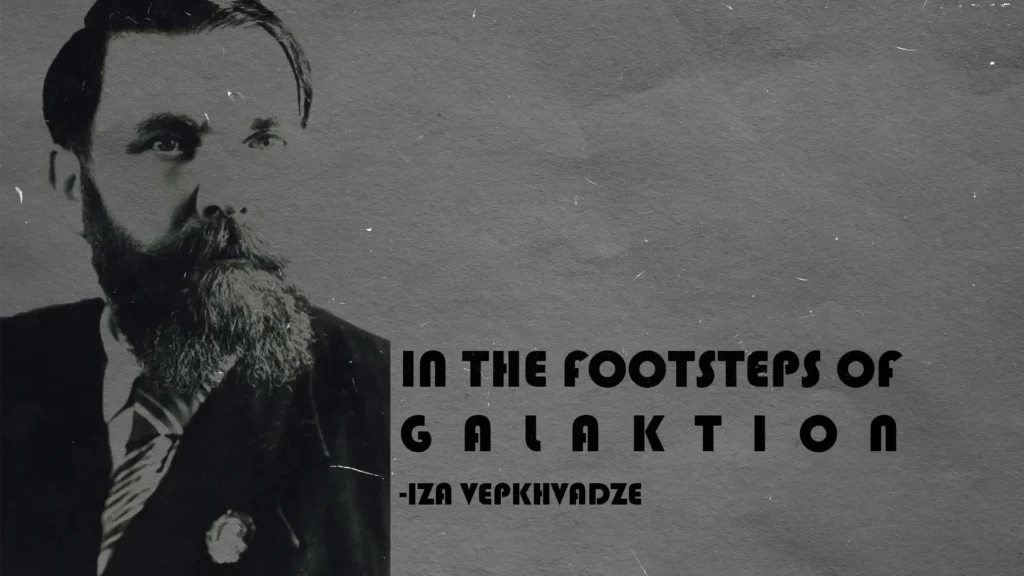

Author: Iza Vepkhvadze

Early spring of 1910 in Partskhnali…

A man in festive attire awaited someone…

At that moment, he invigorated in his mind the nature of the yet unseen place of Partskhnali to a familiar tune:

“Soon the bleached

The forest and field will be green,

Flowers will bloom

Spreading fragrances;

Laurel trees will come alive,

The mountain’s peak, the forest’s mouth

And there will pass

The spring zephyr.” (literal translation)

This was preceded by unusual news:

In 1909, seminarian Galaktion Tabidze became a staff member of the magazine “Faskundzhi.” He also contributed to the magazines “First Wave,” “Georgian Moambe,” and the anthology “First Step.”

Galaktion, passionate about literary work, grew disillusioned with the seminary.

This disenchantment intensified when, on January 18, 1910, his close friend and fellow seminarian, Dimitri (Kuchu, Demon) Kavtaradze, committed suicide. This event had a devastating impact on Galaktion, leading him to leave the seminary heartbroken and, after several years apart, return to his native village—Chkvishi. His mother and brother, deeply invested in his education, were dismayed by this and even had serious disagreements with Galaktion.

He was engulfed in terrible sadness, all exacerbated by extreme poverty.

This necessitated seeking a means of survival, leading him to approach the school’s headmaster, renowned historian Tedo Jordania, hoping to be placed somewhere as a teacher.

Soon Galaktion’s request was granted, and he went to Shorapani. He was appointed as a primary school teacher in the village of Partskhnali in the spring of 1910.

On his way from the village of Kharagauli to Partskhnali, at a crossroads, he paused for a moment. He felt someone’s insistent gaze; it was Nikoloz Buachidze, a young man from Partskhnali, a companion sent by God to Galaktion.

He introduced Galaktion to the village priest, Kirile Kelengeridze. Kirile welcomed the guest warmly, though neither the guest nor the host knew then that “immortality itself” had stepped onto the blessed land of Partskhnali.

18-year-old Galaktion Tabidze, a primary school teacher in Partskanali, settled in the house of Dimitri Haradze in the Haradze district of the village. No one knows for sure why Galaktion chose to live in this area, a whole mile and a half from the school. Still, anyone who has seen the surroundings of Partskhnali would surely notice the uniqueness and diversity of the Haradze district’s nature.

Galaktion chose the smallest and coziest room in the Haradze house. Its splendor consisted of a table, a bed, and a chair.

It had one window, through which there was a beautiful view of the village.

It remains today as it was then, in Galaktion’s times;

Even today, family members tenderly open the door to the room, as if the figure of Galaktion might once again step out from there.

Galaktion has one undated poem, written in the early period, which somehow reminds me of Galaktion, looking out of the window of the Haradze house:

“Here is the window of that house,

an unforgettable window

from the novelty of that time

Nothing remains in my heart.

forever from this moment

this door is closed,

From where light emerged and

The rising dawn! “ (literal translation)

The Partskhnali primary school was located in the middle of the village, in the churchyard, in a rough wooden hut. The school’s inventory consisted of carved wooden desks and chairs, where a dozen children sat: Ermaloz, Afrasion, and Soso Buachidze (Soso Buachidze later became a great general and military figure), Minago and Mitiya Tabukashvili, Maro Sakhvadze, Paco Kiknadze, and several others.

These ten students had two teachers: Galaktion Tabidze and a theology teacher, Deacon Simon Haradze. Even today, people in Partskhnali speak of his exceptional kindness.

Did Galaktion love children? One day, Ermaloz Buachidze, Galaktion’s favorite student, did not come to class. After lessons, Galaktion visited his family to find out why. Ermaloz’s mother apologized, saying she had washed his only pair of pants and they hadn’t dried in time, so he missed school. Galaktion pulled 50 kopecks (coins) from his pocket and asked the boy’s parents to buy him another pair of pants with it. Galaktion often organized literary evenings in the village and read poems, and these events were attended by children, their parents, and villagers. Galaktion educated his audience about poetry, literature, and art, and instilled a love for the Georgian language and literature. Teaching became a very honorable occupation for Galaktion, as evidenced by his poem “The First of the Month of Enkeni” (an old Georgian name for the month of September), published in the journal “Ganatleba” in 1911:

“People unfortunate! I hold a candle

The teacher shall not succumb to a harsh fate!” (literal translation)

In 1910, a convention of rural teachers was held in Kutaisi, which Galaktion attended. At the convention, he delivered a fiery speech and condemned the policy of excluding the Georgian language from schools: “They tell us not to teach the Georgian language in schools, and we tolerate it, and—whom do you want to be? Why be Georgian, if someone tells us, he probably won’t survive. It’s the same: if we don’t have the Georgian language, we won’t be Georgians either.”

Along with teaching, Galaktion worked diligently on himself, constantly reading, writing, and reflecting. During this period, many of his poems were published in journals and newspapers:

“To a Woman-Actress,” “Poetry,” “Only Nature,” “Parvana,” “My Muse, You Also Have a Soul,” “Bitter Sadness Does Not Leave Me,” “Morning,” “Music,” “Autumn,” “In a Flowering Garden,” “In the Forest,” “Rain,” “It Sounded Among the Fields,” and many others.

The poet wandered in deep thought through the beautiful surroundings of Dimitri Haradze’s house. While captivated by the immobile mountains, who knows what thoughts visited him, what feelings were in his soul… Nature celebrated, rejoicing, birds on spruce branches proclaimed to the poet the triumph of nature:

“The spruces smell

like tender pain

Here neither wander nor walk

The noise and clamor of the streets.” (literal translation)

In this comfort of ravines lost on mountain slopes, like an old man, the fog perpetually spoke of the beauty and eternity of nature:

“What does the ravine remember,

through many centuries,

What thinks the forested mountain,

lying like Devi—a giant.” (literal translation)

In the morning, Galaktion left papers with still-wet ink on the table and rushed to school. History and memory tell us only of the contents of several letters to Raisa Chikhradze, the owner of his heart at the time:

“Hello, Raisa!

Are you okay? What news in Kutaisi? What’s in the newspapers? I haven’t read them for a long time. The only thing new here is that I’m writing a poem… I have a heroine named Raisa (do you mind?) I’m very sorry that I couldn’t travel to Kutaisi, and couldn’t bring you what I promised, but let it be next time.

Soon to be printed.

Goodbye. Your respected G. Tabidze:

January 14, 1911.”

In the village of Partskhnali, they still say that Galaktion chose to live in the Haradze district because the beauties of the village used to live there. Who knows, perhaps it was not so, and the village gossips certainly knew that the unmarried daughters of the Buachidze and Haradze families—Nina, Mashiko, Ivlite, Donika—were drawn to the young teacher. They washed clothes all day at the village spring, where Galaktion passed on his way to school. The young women washed to catch Galaktion’s attention. Seeing this, Abesalom Buachidze joked, “This village teacher has taught these girls to wash.”

One morning, when Galaktion entered the schoolyard, he was greeted by an unpleasant sight: a five-year-old linden sapling, planted in the churchyard the evening before, had been blown away by a strong wind. Galaktion began digging in the earth. At that moment, his student Ermaloz Buachidze entered the yard—Friend, can you find me a stick somewhere?—asked Galaktion, threw soil around the linden’s roots, then attached a stake to it and tied the sapling. After that, he especially took care of the young linden, watering it. In the village, this linden is still called Galaktion’s linden, and for some reason, this tree stands out among other trees and has a wide trunk.

It is not surprising that everything touched by Galaktion, his pride and grandeur, should overshadow other trees. During his time in Partskhnali, one incident forever remained in the poet’s memory, which he always recalled with pleasure: “… when I left the seminary, I was given a teaching position in a village near the Kharagauli station. On Sundays and holidays, I came from the village to the station, where my fellow teachers gathered…

In the evening, the train from Tbilisi arrived, and this was also a kind of pleasure for us. Suddenly, someone familiar might get off the train, bring us news from Tbilisi, or tell us something about acquaintances. One day I stood at the station for a long time… we talked, laughed… the train approached. A group of young women stood and watched the passengers.

At that time, a second-class train window lowered. An old man with a face as white as cotton, with an Olympian proud face, looked out of the compartment, like a god…

-Akaki! – someone said.

This word acted on everyone like electricity. We stood for a while in awe, I stared at this face, Akaki read the name on the station building and closed the window again. I can see him sitting down in the chair. Everyone rushed to that compartment… Some wanted to enter the train… At that time, the train screamed, gave a third bell, and moved along the smooth, sharpened rails,… I followed the train at a slow pace. … Then I stood for a long time as if deafened.”

Often, very often, Galaktion stood on the platform of the cozy Kharagauli station, surrounded by the shade of tall poplars, and did not then suppose that his standing there would be written in golden letters in the history of the small platform of the Kharagauli station. Enchanted by the tranquility of the cozy station and filled with a sense of anticipation, the poet recorded in his notebook beautiful lines and forever immortalized the Kharagauli station.

“I remember in Kharagauli

a sad station,

its treasure—

crumbly brick.

A carefree life

quiet as a cuckoo

I hear the approaching

Hum of a train” (literal translation)

No one knows why… One day in June 1911, Galaktion decided to quit teaching at the school, to abandon this “detestable” coziness, and to join the turbulent flow of life:

“Today I hate the cozy shore—

nothing more;

I crave the direct wind,

nothing more.

I crave the black night

Crave a simple boat,

Oh, boat, boat, boat I crave,

one oar and

nothing more.” (literal translation)

Galaktion left the cozy shore and sought a boat that would sail into the thick of life, turn everything upside down, but most importantly—

“Let the wind blow.”

“It was no ordinary day when Galaktion left Partskhanali, just as the day he first stepped onto this land could not have been ordinary. Whether it was pouring rain or a storm was breaking trees, the cozy Kharagauli station pulsed like a living creature, awaiting the hum of the approaching train… Yes, ‘the train is about to depart,’ it will carry away the ‘Unusual’ passenger and leave a bright ray in the everyday measured life of Kharagauli, leaving traces of his steps, which are still visible on the blessed land of Partskhnali.