Author: Mariam Mebuke

“A character lost in the chaos, trying to turn life into one big movie.”

You probably won’t recognize this phrase—it doesn’t belong to a famous director, writer, or poet. And this article isn’t about French cinema or the aesthetics of Tarkovsky, Kubrick, or Parajanov. Yet, one thing is clear: there’s a poetic quality to his films and a search for the cinematic within everyday life. We are talking about a young, twenty-year-old filmmaker from Rezo Gabriadze’s Imereti, a place dear to our hearts. This is Saba Bodokia, a man in love with cinema, slowly proving that the dream of creating a flying machine isn’t so far-fetched when fueled by imagination and a desire to soar.

Watching one of Saba Bodokia’s films offers a glimpse into his inner world—a world of unique visions and offbeat narratives, often difficult to grasp in everyday life. Bodokia is more of a thinker than a talker. He saves his thoughts in a diary, eventually translating them into films. Typically, he is both the writer and director of his scripts.

At the age of 15, Saba penned the script for his first short film, Self-Portrait. He also served as the cameraman, shooting the entire film on his mobile phone across all four seasons. This early project provided invaluable experience. Self-Portrait can be described as an unspoken protest against the erosion of time—a rebellious exploration of freedom that aims to dismantle the old to make way for something new. During the premiere, Saba remarked, “Many people probably didn’t understand the essence of this film, but if they did, it would be good for our society.” His words underscore the film’s complex, uncomfortable, yet ultimately truthful expression of dissent. Even today, protest through art remains powerful, particularly when voiced by a new generation.

The film begins with birth—the moment when a person is granted the “right” to perceive themselves as part of society. Whether this is a privilege or an unwanted process is a question the audience must ponder throughout the film. It tackles profound truths, layered with an emotional intensity rarely seen. The story begins with the formative family unit and then moves toward the process of socialization. Throughout the film, people are symbolically covered with cloth, reinforcing society’s compulsion to homogenize individuals. The saying “everyone should not be cooked in the same pot” feels irrelevant here. Eventually, there is an awakening, a shift in perception, like a dream or an escape from the rigid world imposed upon those who dare to be different. The dream becomes a mode of survival, but tragically, it grows increasingly difficult to sustain. Then, a gunshot pierces the air—will you wake up, or be lost forever?

In another scene, we witness a “Kelekhi” (a funeral feast), a common tradition in Georgia, with faceless mourners grieving alongside a mother who has lost her child. From birth to death, everything changes only for one person—the rest remain the same.

Beyond the narrative, the film pays homage to art in other ways. Iconic paintings come to life on screen—René Magritte’s Son of Man, John Everett Millais’ Ophelia, and a scene reminiscent of Salt for Svanetia (a 1930 Soviet-Georgian silent documentary by Mikhail Kalatozov) with shadowy figures. As Saba’s experience with filmmaking deepens, his visions evolve. From his early work at 16 to now, as a third-year film student, his growth is undeniable. An artist’s greatest challenge is the constant pursuit of innovation, a goal Bodokia wholeheartedly embraces.

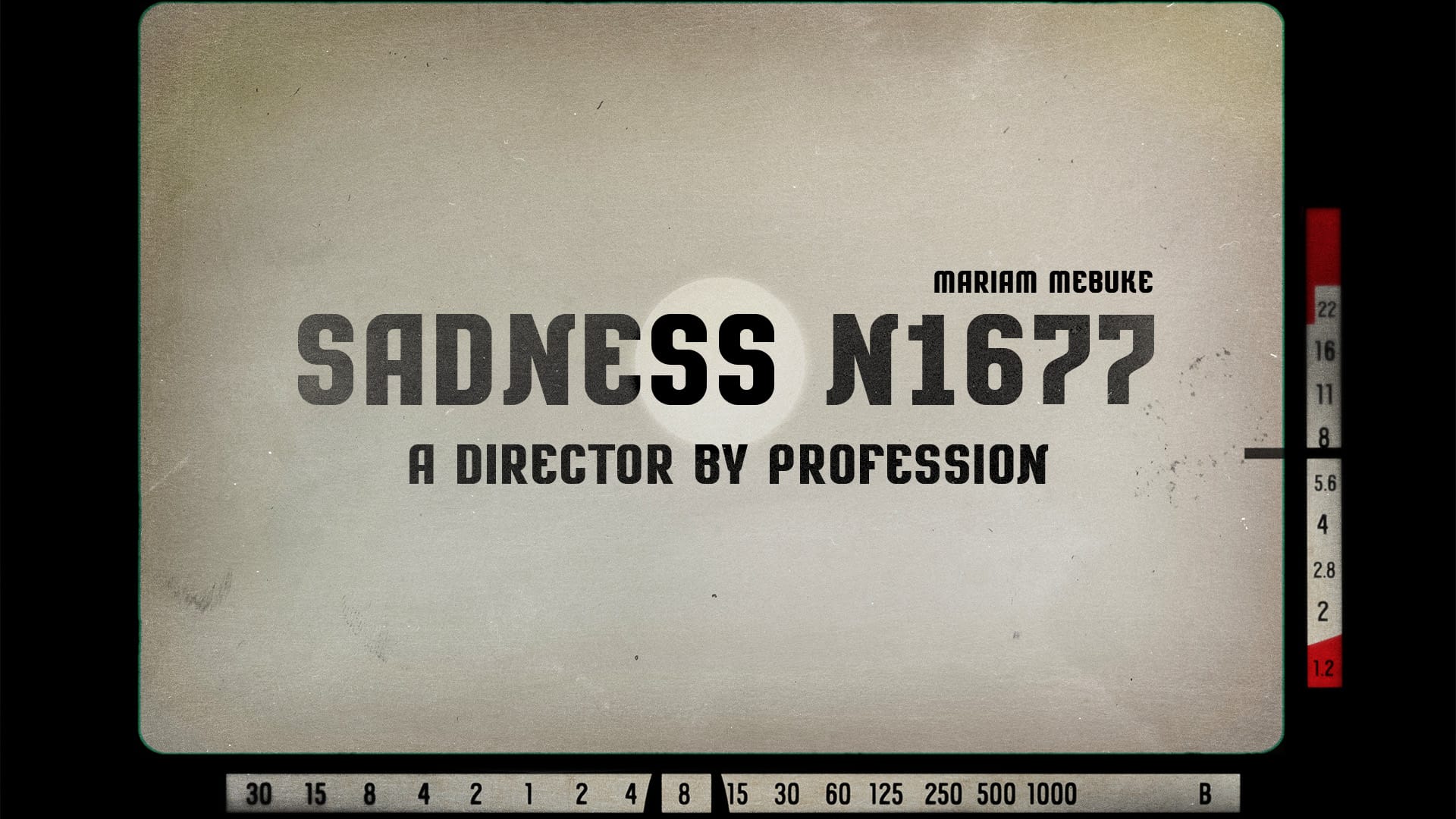

In his recent short film Sadness N1677 (inspired by Goderdzi Chokhel’s The Sadness of People), Bodokia tackles deeper existential themes, weaving historical narratives from wartime to the modern feminist movement, evoking the “voice of the Georgian woman.” Though his films are short, they leave a lasting impact. Bodokia’s work is layered, inviting contemplation long after the credits roll.

Bodokia has also ventured into documentary filmmaking. His recent film The Tree of Desires premiered at the Telavi Film Festival. The film showcases his ability to spotlight the unseen, focusing on the lives of displaced children living in an old sanatorium in Tskaltubo. Even in his documentary work, Bodokia never loses his poetic touch. This film transcends the genre, blending art with everyday struggles, particularly the hardships of war. As with all his work, the film’s title is symbolic, and well thought out—just like his earlier Self-Portrait, which delves into the search for salvation for those like him. The title of the latest film signifies the return of something that has been spoken about a thousand times — the return of what, as Chiladze writes in one of his poems, “was given up by us, not of our own will.” The characters in the documentary are so natural that the final shot evokes a desire to take a train ride along those old tracks. That’s how the film ends. To this day, no one knows when a train will pass through here again.

Another standout documentary is Housewife from Geguti, where Bodokia turns his lens toward the challenges faced by women in Georgia. The film centers on his grandmother, an elderly working woman who, with sunburnt skin and tired hands, reflects on a life of pride and sadness. The film offers a feminist perspective on the obstacles women have faced for generations.

Technically speaking, the progress from Bodokia’s first film to his most recent work is clear. His growth is a testament to the transformative power of artistic dedication. Each of his films is a labor of love—a journey through sleepless nights and rewritten scripts—yet, despite the challenges, the work survives, and so does the message.

Whenever I encounter individuals like Saba, I’m reminded of Carlo Kacharava’s words: “I just wanted to say that this desert I dream of is my own painting, and I live here.”

My goal remains the same – to let more people know about this dream, this desert of unspoken longing.