Kultura! – Article Archive

The Blue Horns: Beginning and End

Exactly a hundred years ago, in Kutaisi – one of Georgia’s oldest cities – a group of young symbolists was formed. They were given the unusual name “The Blue Horns.” The color blue has long been an emblem of Romanticism and Symbolism. It first appeared in a dream of Novalis. The Romantics sought a mystical blue flower, as mysterious as the Holy Grail of medieval Christian knights. Later, the Symbolists adopted blue as the sign of a distant, boundless, and otherworldly world – the realm of spirits, which in everyday language also meant death. The symbol of happiness, the blue bird, was sought by the siblings Tiltil and Mytila in the famous play by Maurice Maeterlinck. Interestingly, this play was…

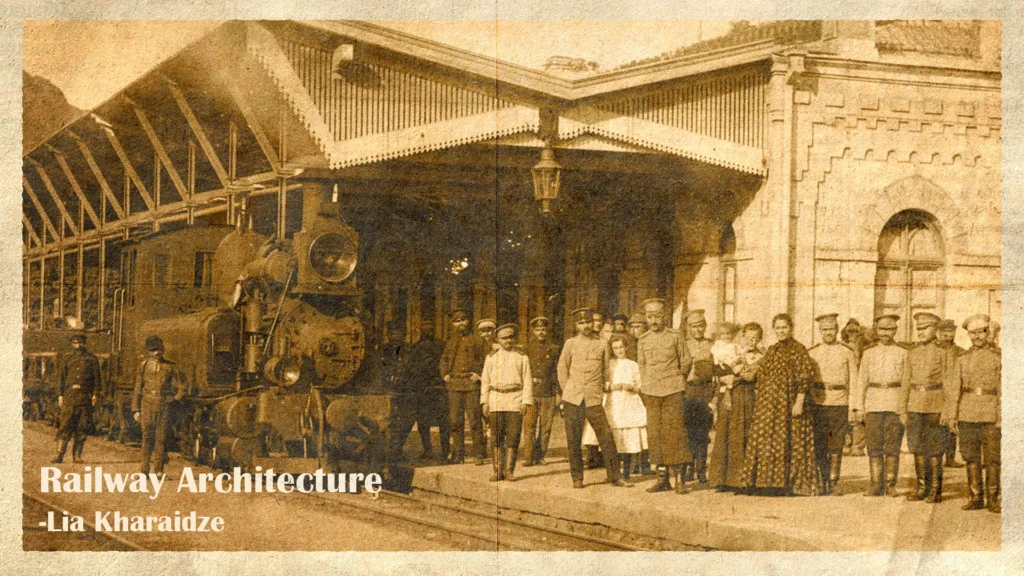

Railway Architecture

The discovery of manganese ore in Chiatura in the 19th century had a major impact on the development of the Imereti region. It gave a strong push to the creation of new transport links and the growth of industrial sectors in Georgia. The rapid development of production naturally led to the rise of an industrial culture. The importance of industrial heritage is widely recognized internationally. Its study, preservation, adaptation, and conservation are a priority in the cultural and research activities of many countries. Georgia has a rich cultural heritage, which has been studied in many directions. However, the country’s industrial heritage still remains outside the focus of professional research. Architectural and engineering buildings and structures built for industrial purposes in…

Vice-Chancellor’s Imereti Life

There is a saying: “When the cart turns over, the path will appear.” However, even after more than two centuries, the turbulent events of the 18th and 19th centuries still leave people wondering: what could have been the best way to save the country? Georgia, a small and divided land caught between three empires, found itself in the middle of a difficult political storm. This struggle had its heroes—and its anti-heroes. One of the true heroes of this period was Solomon Lionidze. He is remembered as a deeply educated and loyal statesman, devoted to his homeland. In the words of historian M. Dumbadze, “…a diplomat and a universally recognized wise man. Solomon rose to prominence not only as a man…

Lado Asatiani’s Girlfriend

Let me tell you about the young woman to whom Lado Asatiani dedicated his famous lines: “Oh, don’t think that beauty is fueled by love or hatred…” While working on the bibliography of the March 21, 1941 issue of the newspaper Industriuli Kutaisi, I came across a small notice of sympathy from acquaintances and friends. It read: “S. Vachnadze, M. Tutberidze, L. Asatiani and Sh. Kuridze express condolences to Keto Khonelidze on the passing of her father, Justine.” As soon as I read this statement, I immediately recalled the small memoir There Was a Young Man, There Was a Blizzard by Lado’s classmate and friend, journalist Shota Kuridze, published in the 1980s by the Soviet Adjara publishing house. Several pages…

“If I go, I will go, will go and go”… The Remarkable Story of Friendship and Self-Sacrifice between Lasha Lashkhi and Obola Tsimakuridze

It was a memorable day in Sachkhere – people were celebrating Akaki Tsereteli’s birthday. After the official event, we were sitting at a traditional Imeretian table with the then-mayor of the municipality, Tsezar Lashkhi. We were in the middle of breaking bread when Mr. Tsezar received news that his eldest son, Lasha, was unwell. But it wasn’t just illness. It turned out that he was… no longer among the living. That day marked the beginning of a sorrow that has now lasted 25 years. It was a quiet afternoon on June 21, 2000. Two friends from Sachkhere – famous parodist Obola Tsimakuridze and researcher at the Georgian Museum of Art, Lasha Lashkhi – were walking together, reminiscing, talking about the…

Lampreduzo Meduso! – Thursday Cinema

Even though I’ve spent years living in Kutaisi, I still come across interesting facts and stories about places I’ve passed by many times and wondered about. This probably happens because I wasn’t born in Kutaisi in the 20th century. At the start of this article, I’d like to point out one thing – I’m mainly trying to catch the attention of readers my age, those born in the 21st century, who know Georgia’s past mostly from stories told by others. The word “Radium” is likely familiar to everyone as the name of a chemical element. But for those who have ever walked along Tsisperkantseli Street in Kutaisi and glanced – even for a moment – at the building in front…

Kutaisi in the 1920s: Memories and Lost Stories of the Repressed

Dori Laub, a psychoanalyst and professor at Yale University, developed important insights while researching trauma and how it is shared, expressed, and listened to. According to him, when a person shares their inner pain—something not yet fully understood or expressed—with another person who truly listens, a unique and deeply emotional situation is created. What makes this experience so extraordinary is that the listener is not hearing a story already told in museums or recorded in archives. Instead, they witness something being born for the first time—pain that has never had a chance to be revealed before. Historical facts and context are present, but they do not reduce the importance of the listener. Instead, they offer a backdrop. The act of…

New Fashion: From Bandeau to Pearl Necklace

When discussing the cultural developments of the late 19th and 20th centuries, fashion must be mentioned as one of the key indicators of a society’s cultural life. Kutaisi, in particular, played a significant and fascinating role in the history of Georgian fashion. The production of silk fabric in Georgia is closely connected with Kutaisi. In 1889, in the Kutaisi province, the country’s earliest spinning factories were opened – two small mills both known simply as the “Spinning Factory.” Kutaisi was the main center for silk production, and the fabric was sold at fairs across Georgia. These locally produced materials were quite expensive – their total value reaching up to 75,000 rubles. At the end of the 18th and beginning of…

Epitaph

The saddest, most mysterious, and strangely fascinating place — a cemetery — often stirs many thoughts and memories, creating an atmosphere ripe for philosophical reflection. For centuries, people have expressed the grief of losing a loved one in different ways. One of the most lasting expressions is the creation of a grave — an “eternal resting place.” Memorial monuments have changed over time, reflecting different historical periods and cultural styles. Tombstones can tell us a lot — not only for professional researchers but also for amateurs or simply curious visitors. Many scholars focus on epitaphs as valuable written sources, while the artistic side of gravestones and monuments is less often studied. This article does not aim to be a scholarly…

Chiatura – The Beginning of Georgian Tennis History

The golden rays of the sun gently touch the old cobblestones, while the air carries the scent and color of manganese. Between stone houses, in a narrow courtyard, a curious sound is heard – the crisp echo of a ball striking a racket. At first, it seems unfamiliar to the locals, but soon it draws their attention and fascination. The story of tennis in Georgia begins in Chiatura at the end of the 19th century – a time when the country was still part of the Russian Empire, and foreign cultural influences reached only a few places. During this period of industrial growth, the work of the English company “Forward and Salinas” in Chiatura played a key role not only…