Kultura! – Article Archive

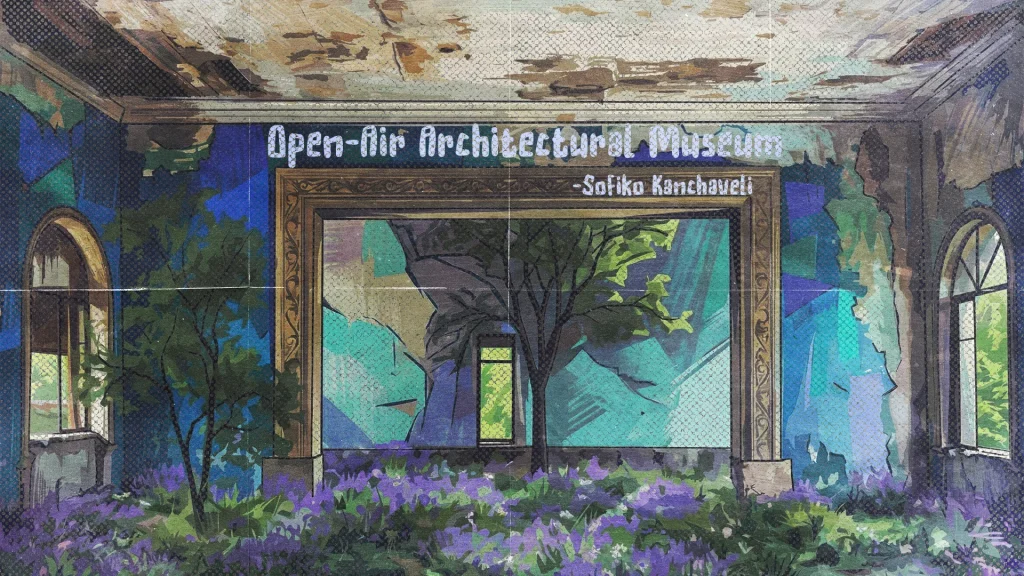

Open-Air Architectural Museum

This city has a soul – aristocratic and somehow majestic. It has color: a mixture of plants and sunlight. It has strict geometry, both curved and twisted. In the 1950s of the last century, sanatoriums built for the recreational function of the city, officially designated as a resort, appear today as conceptually significant architectural masterpieces representing different stylistic trends. Just a few years ago, the city – an origin of form, light, and the rebirth of nature – inspired actor Jim Carrey to purchase a moving NFT artwork created by Swedish artists Ryan Koopmans and Alice Wexsell. The work depicts a room in an abandoned sanatorium in Tskaltubo and is digitally processed as if the forces of nature had prevailed…

City and Memorial Space as a Form of Urban Memory

The study of cemeteries and the system of meanings associated with them in the urban context is a highly topical subject in modern social and cultural anthropology. In addition to their practical and ritual functions, cemeteries have acquired important symbolic meanings within urban space, which are interpreted differently by various authors and theoretical approaches. In this brief analysis, I will discuss several perspectives on the symbolic load and social understanding of cemeteries as elements of urban space and will connect these considerations to the local context of cemeteries in Kutaisi.

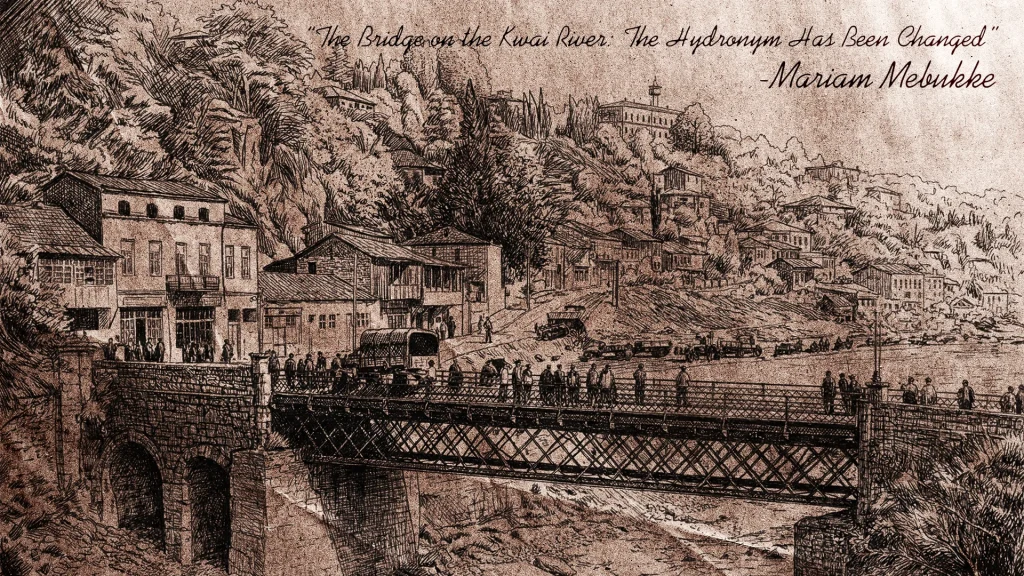

The Bridge on the Kwai River: The Hydronym Has Been Changed

It is often said that the history of Kutaisi is rooted in the city’s rich antiquity and culture. Recently, I came across a work by the artist Gocha Chkhaidze called House on Tsereteli Street. That is why I decided to talk about the architectural character of Kutaisi in this article. Part of the city’s culture consists of its buildings, bridges, and overall urban style, which often escape our attention. This time, let us look at the history and significance of the famous bridges of Kutaisi. When I speak to friends visiting the “City of White Stones” for the first time and want to tell them about its architectural value, I usually begin with the Shota Rustaveli Bridge, the White Bridge,…

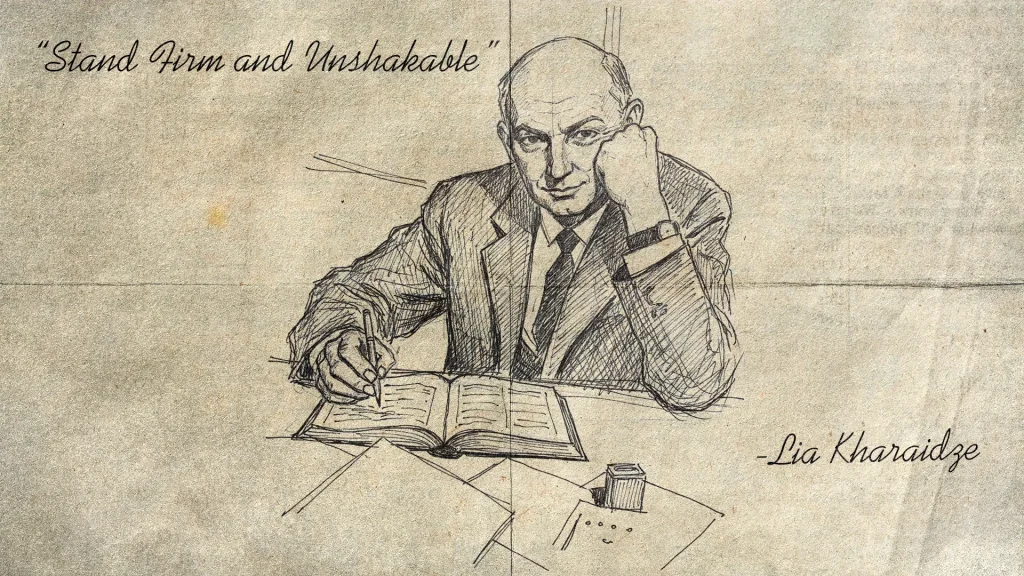

Stand Firm and Unshakable

In Chiatura Municipality, there is a small village of 180 households – Tskhrukveti. Although modest in size, it would be difficult to find another village that has given so many scholars to the homeland at the same time. It is here, in a picturesque setting, that a beautiful oda house – a type of traditional Georgian mansion – stands, bearing the name of Academician Giorgi Tsereteli for the past forty years. In earlier times, the Tsereteli Palace stood on this very site, serving as a gathering place for the Georgian intellectual elite of the 19th and early 20th centuries: Akaki Tsereteli, Galaktion Tabidze, Niko Nikoladze, Ivane Varazashvili, Grigol Zdanovich, Konstantine Abashidze, and others. Although this historic residence was later destroyed,…

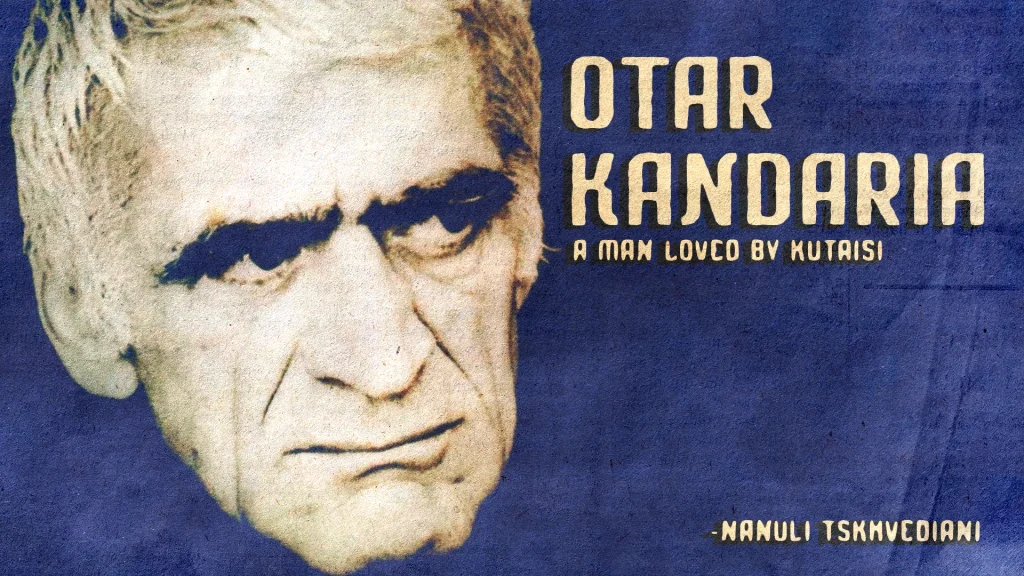

Otar Kandaria – a man loved by Kutaisi

Whenever he appeared, everyone on the street would follow him with affection – a calm man, always in a black shirt, with a suit casually thrown over one shoulder. The light in his large eyes could not be hidden even by his thick eyebrows, and yet there was a quiet mystery in the strict lines of his face and in its characteristic expressions. Once, director Geno Chiradze filmed the artist in a short episodic role, preserving these features, this voice, and these elegant manners forever in the film Zvaraki (1990). In the film, the role of Otar Kandaria was originally meant for Levan Abashidze, who played the main character, but the personal charm of the newly recognized Kutaisi artist was…

In the Footsteps of the Scattered Treasure

The history of the Argveti Saeristao begins with King Parnavaz. “…Was sent to Margvi as Eristavi and gave him a small mountain, which is Likhi, up to the sea above the Rioni. And this Parnavaz built two fortresses.” (Vakhushti, Description of the Kingdom of Georgia.) According to Leonti Mroveli, the Argveti Saeristao included the territory from the Likhi mountain to the Rioni and from the Racha mountains to the Fersati mountains. The rise of the Baghvash-Orbeliani dynasty began after they took control of Kldekari together with the Argveti Saeristao. Kldekari, as a border domain, was extremely important strategically because it was truly the gateway leading from Byzantium into the heart of Georgia. Both allies and enemies understood this well. The…

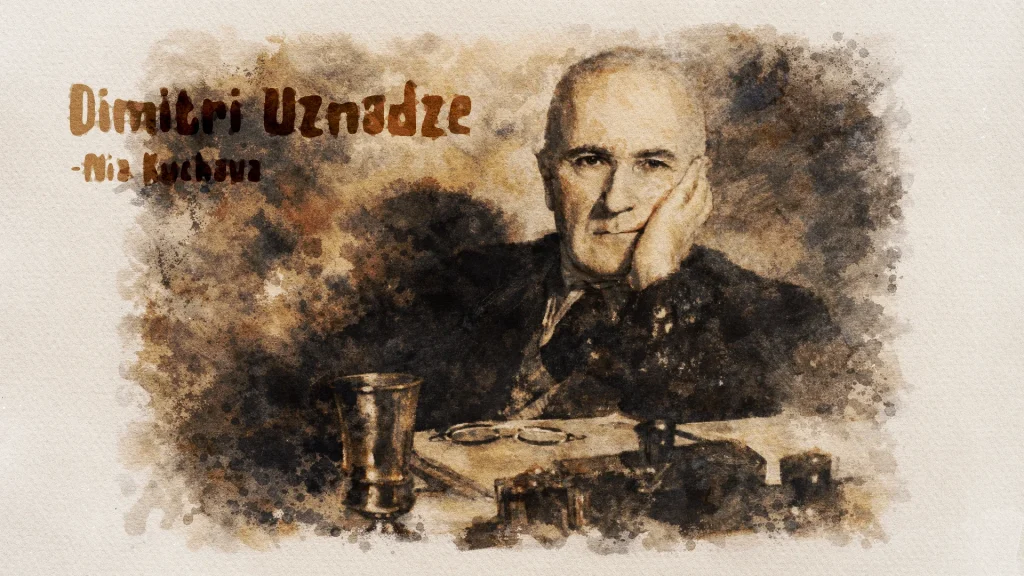

Dimitri Uznadze: Theory and Practice

Dimitri Uznadze’s academic work has been one of the key factors in the development of the Georgian school of psychology. His pedagogical approach and research methods are especially important both for the development of Georgian academic discourse and for the international scientific community. The theory of “set” (or “attitude”) formulated by Uznadze, as well as the methods with which he studied the unconscious, were largely based on his European education and his relationship with Wilhelm Wundt, the founder of experimental psychology. However, alongside continental psychology and such important thinkers, there is a less emphasized, though no less significant, direction in the work of Dimitri Uznadze. His pedagogical and research activities were also influenced by his work in Western Georgia, and…

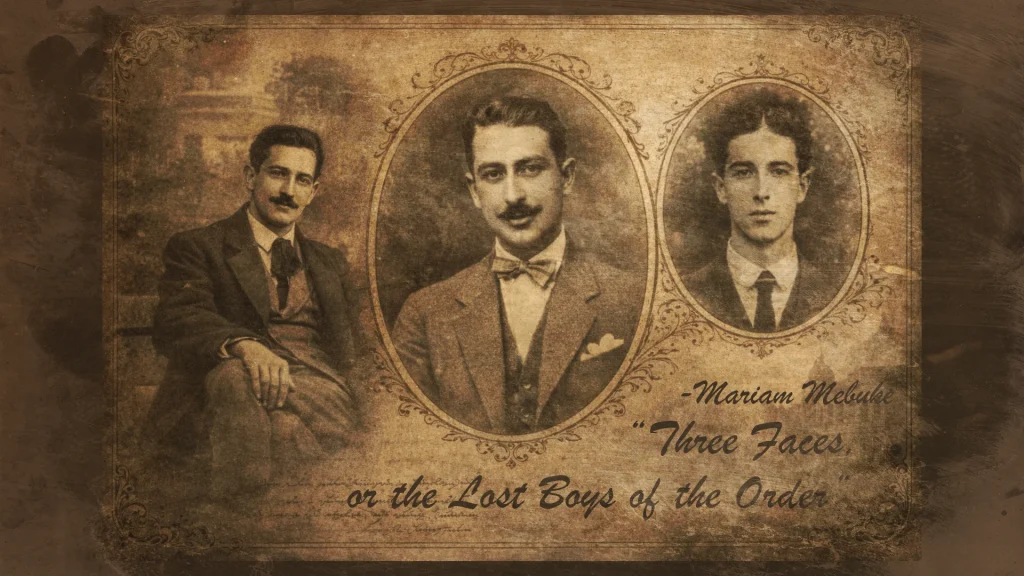

Three Faces, or the Lost Boys of the Order

Every year, a strange spring arrives in the city of white stones. That is why we say that perhaps not one swallow, but the blooming magnolia at the “Red Bridge,” can definitely bring it. Kutaisi has never demanded more than the love of its inhabitants. Despite this, “falling in love at first sight” with the city was always special and emotional. It was easier for those who connected their creativity with this place. Probably, none of them looked for a muse elsewhere. Women went out to see the newly blossomed magnolia, including those who broke the rules of their era and walked the streets of Kutaisi with a cigarette in their hand. Our story should start from here… The city.…

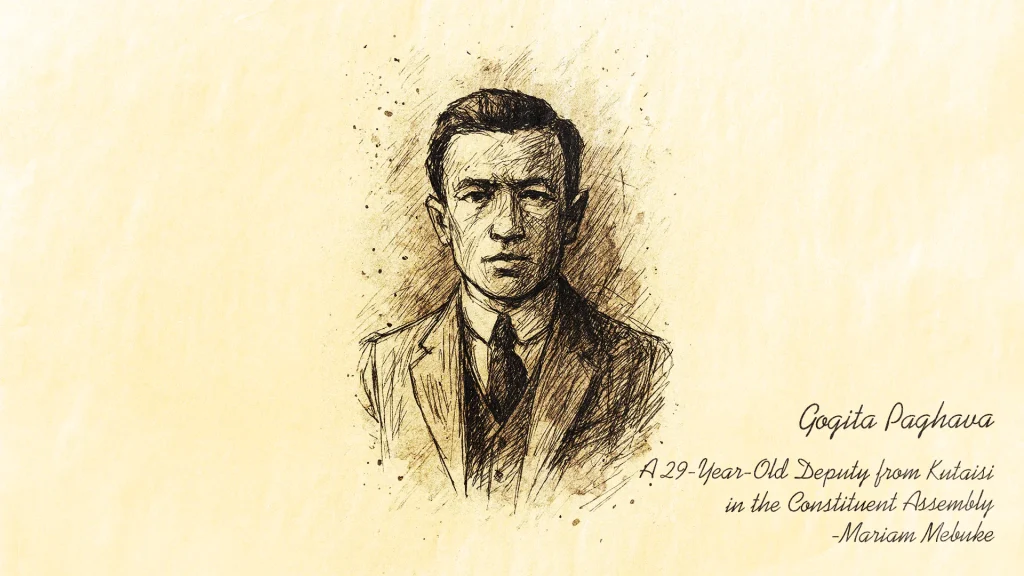

Gogita Paghava – A 29-Year-Old Deputy from Kutaisi in the Constituent Assembly

The rethinking of the idea and significance of the First Republic of Georgia began rather late, as for a long time, Soviet propaganda had tried to erase its leaders and important political figures from public memory, distorting the image of the First Republic itself. This time, my goal is not to discuss Georgia in 1918–1921 in general, but to speak about one of its remarkable and almost “disappeared” representatives – Gogita Paghava, the youngest deputy of the Constituent Assembly, who was executed at the age of 29. However, before that, it is necessary to set the background.

In the Tunnel of Time – The Road from Bondi Cave to Civilization

Upper Imereti, and especially the Chiatura municipality, is one of the most significant archaeological regions in Georgia. The cultural layers formed here over millennia fully reflect the continuous development of human civilization. In Chiatura, the naturally enclosed canyons and rocky landscape filled with caves create a unique environment that preserves evidence of material culture from the Old Stone Age, Neolithic, Eneolithic, and Bronze Ages. There has always been life in the caves of Chiatura. The people who lived here protected themselves from predators, wove and dyed thread in simple ways, worked stone, made primitive tools, and left us a legacy – a history that is still being read underground. A special place in this remarkable chronicle is held by Bondi…