Author: Nanuli Tskhvediani

Jewish traders from Kutaisi and their secret “language.”

Have you ever heard how much the development of commerce and international economic relations of Kutaisi and the entire West Georgia in the 19th and 20th centuries relied on the Georgian Jews?

Some interesting facts can be found in the paper by Ilya Papisimedovi, “On the history of Jewish commerce in Georgia”: it turns out that back in 1866, 62 Jews living in Georgia obtained permission to travel abroad for commercial activity, while in 1867 this figure comprised 44. Based on the surviving records, residents of Kutaisi were the most numerous groups on the list. The Iakobishvili, Eligulashvili, Enukashvili, Tavdidishvili, and Khananashvili families stood out among the first and the second guild traders and on numerous occasions, traveled to Istanbul, Trabzon, Moscow, Nizhny Novgorod, Odesa, Kharkiv, Rostov, Warsaw, Lodz, and other large cities. Local and small traders bought from them in cash and credited the goods imported from abroad. The Jews from Kutaisi exported from West Georgia large batches of goods such as raw silk, pig’s bristle, woman hair, and furs, and sent annually 50-60 wagons of eggs (each wagon fitting 14,400 eggs), 15-20 wagons of feathers, 3-4 wagons of used galoshes, 2-3 thousand items of ancient carpets, lots of fruits and prunes. Some of these traders sold manually knit “Imeretian wool,” which, although known by this name, was, in fact, produced in Samegrelo. Some of these products were sold in Georgia, and others were sold in Russian fairs. While this product faced intense competition from the early 20th century from cheap wool manufactured in Russian factories, it was never short of buyers due to its high quality.

According to Papisimedovi, the second half of the 19th century saw several Jewish traders accumulate enormous capital and gain control of almost all domestic trade. Some of them launched large industrial enterprises and even banking businesses. Many were considered bank members, and some were co-founders of large banks at the beginning of the 20th century. Back then, the press regularly published more than 60 Jewish businesspeople’s names and addresses. Some of them were even elected members of the city municipal government.

According to the data preserved in the old press, while the families mentioned above-owned houses built of white stone, expensive clothes, and jewelry, lived in incredible luxury, and enjoyed high social status, Jewish small traders and their multi-member families, on the contrary, had to survive under heavy social conditions. Not all of them were trading near their home, in the bazaars of Kutaisi – “Didi Kapani” and “Gaghma Kapani.” Many would rush into the streets on early Mondays – drapers, sellers of kerosene, salt, soap, medicines, and kitchenware, with shoulder bags on their backs or with baskets in their hands. If they were lucky enough, they’d have a horse or a donkey that they would load with a cone-shaped “godori” basket, a saddle bag (“khurjini”), or a large wooden box to transport their goods to distant villages. Otherwise, they’d have to carry their goods on foot. These merchants would go on business trips for several days and be back to their families, tired, hungry, and battered, only to start it all over the following Monday.

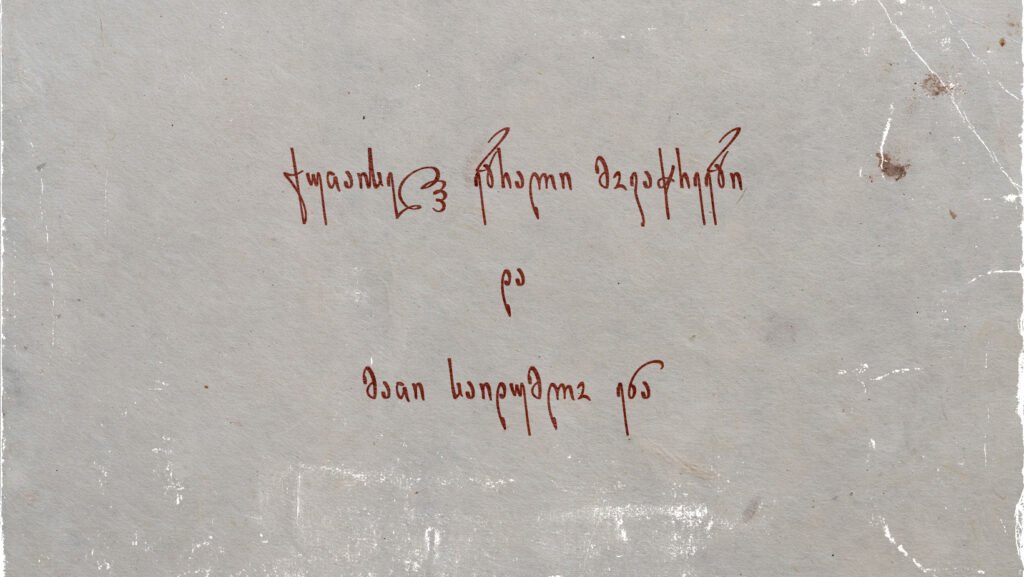

Kutaisi State Historical Museum, along with other documents on Jews, stores an interesting document on a Jewish merchant from Kutaisi. This document is a “discharge request form” addressed to the landlord, Duke Giorgi Tsulukidze (patronymic name -Katsia), asking his permission to let “Daniela Moshiashvili the Jew” leave for the city of Tiflis for three days to trade.

It is noteworthy that Kutaisi Jews maintained their interest in trade in the Soviet era as well. Trade, referred to as “speculation” by law enforcers and the press back in the day, was thriving in the area densely populated by the Jews, especially at the illegal, “underground” market at Shaumyani (presently Gaponovi) Street. However, the area was always at the center of attention, both in the city and neighboring areas. People purchased from the Jews imported goods: textiles, clothes, shoes, utensils, food products, cigarettes, luxury items – all they could not get in the Soviet stores, brought by the Jewish families using their channels and networks from far away.

By the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century – just in the time of the development of trade and commercial relations, a “secret trader language” of the Kutaisi Jews was created. This specific, conventional “language” aimed to maintain trade secrecy from clients. The Jews themselves called this jargon “Kivruli,” which is related to the word “Kibri” (a Jew) (in the opinion of the scholar Ilya Papisimedovi). It was widely spread among traders. While the language was mainly used by Jewish trades at public fairs, it had a less significant, though a certain role in the everyday speech of the Jews. As mentioned by Ilya Papisimedovi, several words from this language were used by a narrow circle of the Georgian population as well, especially in West Georgia, Kutaisi in particular.

These lexical items appeared by adding Georgian prefixes and suffices to the stems of Hebrew words.

Ilya Papisimedovi brings the word “ვისოხარე “[visokhare] as an example. In Georgian understanding, the meaning of the word is “I bargained”. According to the researcher, this jargon word must have deviated from the old Jewish word “sokher” – a merchant. In this case, Papisimedovi thinks that Georgian affixes “vi-” and “-e” are added to the Hebrew stem of the word. The word “გავხრიდე “[gavkhride] is expressed similarly, which in the Georgian understanding means “I sold.” The word “მოვატოვე “means “I deceived (him/her).” In addition, some words are also used in a figurative meaning. For instance, the word “დაუადე “in the Georgian understanding means “give (him/her)”. It must have been generated from the Hebrew word “iad,” which means “a hand.”

In his paper, Ilya Papisimedovi uses 107 such words and their Georgian equivalents as examples. The researcher notes that plenty of simple and complex and simple sentences contained these words. Some such sentences also comprised Georgian words as sentence parts.

Trader Jews used this vocabulary up till recently.

The following phrases with a hidden meaning could be heard at Kutaisi illegal markets at Shaumiani Street and other locations until recent times:

– ყატონი არ დაუქამო! (Don’t reduce a single penny!)

– შენს მამონს მე მივხრიდი და, რასაც მოუგადოლებ, სავახეზო იყოს! (I’ll sell your goods, and let’s evenly share the takings!)

– ჩემი მუშტარი გამიშეყერა და ვერც თითონ მიხრიდა (He stole my client… He lured him away but failed to sell (his goods) to him anyway.

– დღეს ტობათ ვისოხარე, მაგრამ სეფერი არ მიეშამდა და ქელებმა შოხადი წამართვა (Today I had good sales, but I had no license, so the cop extorted a bribe from me) (I. Papisimedovi, 1946, p. 74).

The slang deriving from the Georgian-Hebrew words was even popular among a certain group of young people in Kutaisi back in the 1960-70ies, especially among guys. They had such a good command of patterns of what once was a “secret trade” language that it could be heard among representatives of all social classes and age groups. This group of youths tried to emphasize their high ranking and “sophistication” by using this language and speaking this jargon freely. So such words as ნაშა, გიმელი, განაბი, მიამსევრე, დაბრიდე, ჩათოხლა, ეთომარე, დავიადე were the slang words that needed no translation for Kutaisi youths to understand in their day-to-day conversation.

After the great Aliyah, which reduced the Jewish population in the city, the frequency of usage of the above vocabulary dwindled among the next generations. Nowadays, some of the words occur rarely, although time after time.