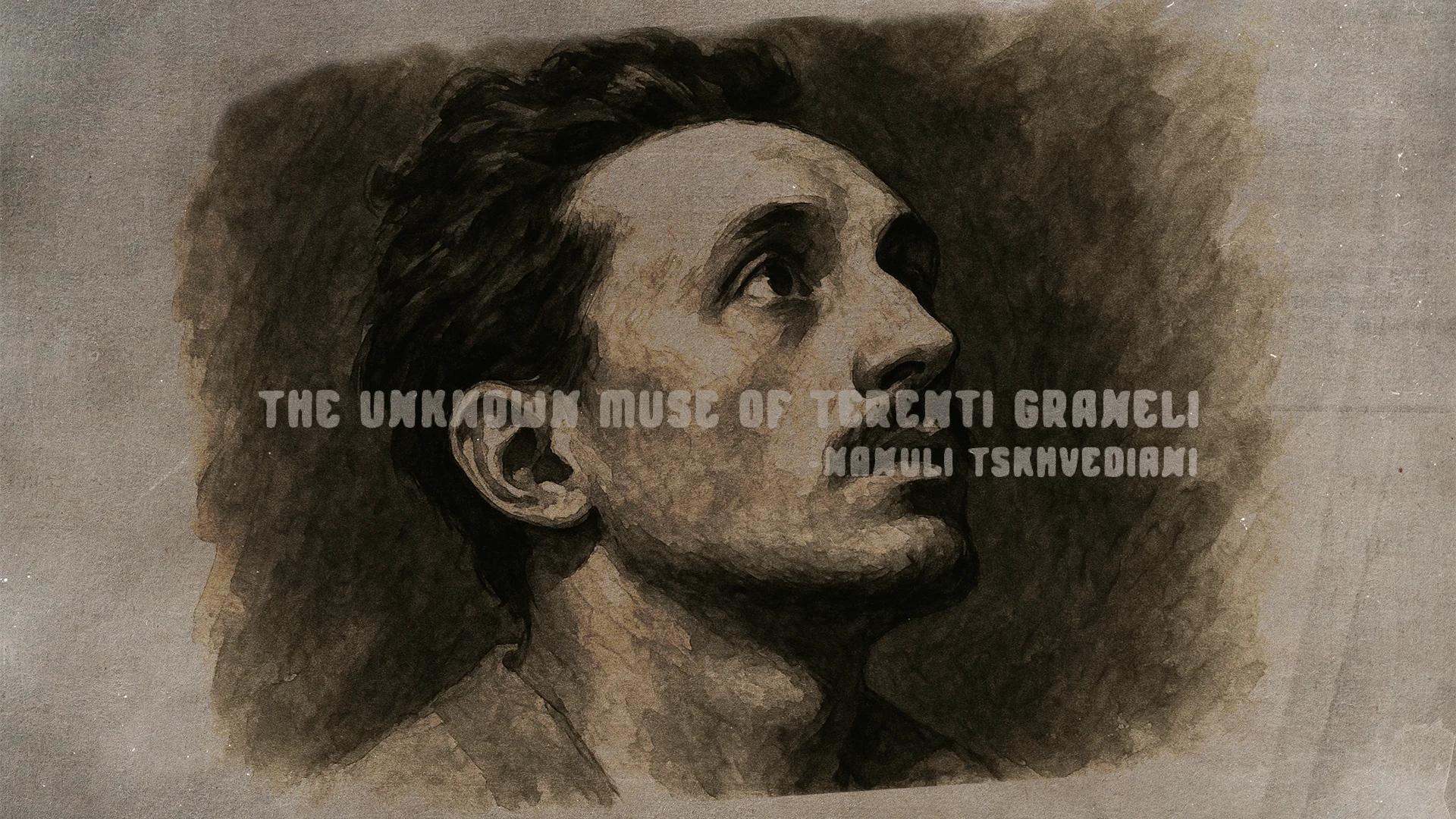

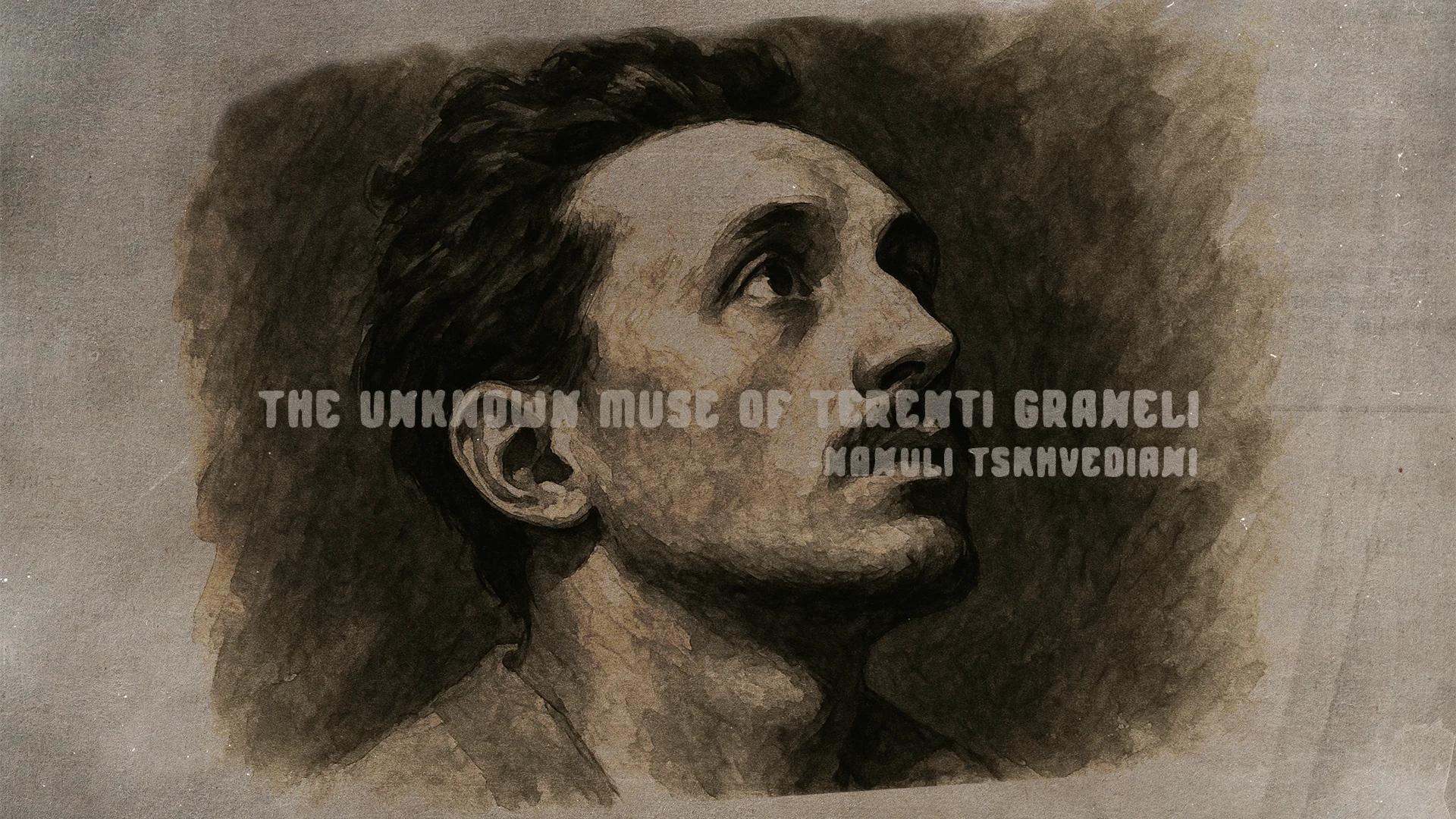

By Nanuli Tskhvediani

Anyone who has read Terenti Graneli’s After Death (“…I will die at night, at dawn…”) will surely remember this passage:

“On Sunday morning, when the church doors open for all worshipers, a woman will come thoughtfully to my grave, she will remember my sunburnt face, she will remember my torture, and she will feel sorry.”

Who was this mysterious woman?

On November 11, 2019, I posted one of Terenti Graneli’s poems on my Facebook wall. A well-known and respected lawyer from Kutaisi, my dear friend Ivane (Vano) Afridonidze, responded with some fascinating information in the comments.

It turns out that the woman Graneli mentioned was Vano’s aunt (his mother’s cousin), Tamar Kachakhidze.

Here are some excerpts from Vano Afridonidze’s comments:

“Once, in 1966, my cousin Tsiala Zhorzholadze, Aunt Tamriko, and I were having a family gathering. Tsiala revealed the secret of that ‘one woman’. We each had a glass of red wine, and she asked her mother: ‘Mom, now tell us about Terenti Graneli’s last request.’

Aunt Tamriko went to her bedroom, took out a triangular letter, and handed it to me.

‘I couldn’t believe my eyes—it was written in Terenti Graneli’s own handwriting!’

The letter said:

‘Dear Tamar, when I die, please do me a small favor. Come to my coffin, stand beside me for a while, shed a few tears, and then continue to live your life.’

‘Auntie, did you fulfill his wish?’ I asked Tamriko.

‘Partially. I was there at the funeral. I straightened the collar of his telagreika (a padded Russian jacket) in the coffin, but I couldn’t cry. When I returned from katorga (forced labor) 11 years later, I found his grave and cried—for Terenti and for my Iliko (my uncle Ilia Zhorzholadze, who had been executed).’”

Vano added:

“If you’re interested in what happened to her after that—yes, there are details, but I don’t think they are relevant to Graneli…”

After Aunt Tamara, the family went through many more hardships. Tsiala is no longer alive. She was an actress at the Kutaisi Drama Theater—she played Ophelia and Desdemona with Bakuchia (Vakhtang Megrelishvili), later became Sergo Zakariadze’s stage partner in more than ten major roles, and eventually became a teenage idol and an Honored Artist of Georgia. She locked the apartment several times, and I’m still searching for Aunt Tamara’s archive—especially Graneli’s triangular letter, letters from Mikhail Kalinin and his wife, autographs of Pavel Antokolsky, Aleksandr Fadeev, Mykola Bazhan, Alexandra Kollontai, Nadezhda Krupskaya, and Lavrentiy Beria, and, most importantly, my aunt’s prison diaries. Nothing is left now except a Becker piano from 1897. Aunt Tamara gave it to me as a gift. It was once sent by Marshal Tukhachevsky as a gift to my aunt while staying in Tbilisi. My uncle Iliko hosted him, and the whole family gave everything to host him properly.

You might ask—who was Tamar Kachakhidze?

She was a lawyer and a second-year graduate of Tbilisi State University. In the 1930s, she served as ideological secretary of the Adjara Regional Committee, later becoming a judge and Deputy Chair of the Supreme Court of Georgia. Eventually, she was appointed as the First Deputy to the People’s Commissar of Education of Georgia, Mariam Orakhelashvili (wife of Mamia and mother of Ketusia). Tamar was also the wife of Ilia Zhorzholadze (head of the Transcaucasian Political Administration) and the mother of two children—Tsiala (the actress) and Lado (a road engineer).

Vano continued:

“My dear Nanuliko, you got me deep into memories, so I’ll tell you this too. Once, after a meeting at the Central Committee, Lavrentiy Pavlovich (Beria) told my aunt, who at the time was the First Deputy People’s Commissar of Education – “Zhorzholadze, should stay.” Tamriko didn’t stay. At the checkpoint, they told her, “The First asked you to remain.” Tamara replied, ‘I’m not Zhorzholadze, Zhorzholadze is my husband. I’m Kachakhidze.’

She already knew that a trap was being set around her husband, Ilia Zhorzholadze.

Beria asked her, ‘Is it true you were the lover of that sly postman, Terenti Graneli?’

She replied, ‘It’s true I’m not Zhorzholadze – but I am the wife of Ilia Vasilyevich (Stalin’s comrade) and the mother of his two children. How dare you! Lavrentiy, you’ll come to a terrible end!’ Then she left his office.

‘I could hear the demonic laughter from the end of the corridor. That’s when I knew what kind of fate was awaiting our family.’

When they came to arrest Iliko, he shouted to his wife, ‘Tamara, divorce me tomorrow – don’t ruin the children’s lives.’

She replied, ‘No, Iliko, I won’t divorce you. You’re innocent and will be vindicated. I won’t betray you.’

The next night, they came and arrested Tamriko too. The children were left homeless, and Academician Giorgi Akhvlediani was given their home on Perovskaya Street.”

Now, about our family background:

Vasasi and Sofio Kokhreidze were daughters of Pavle Kokhreidze from Yaneti (Samtredia). Vasasi married Spiridon Kachakhidze in Didi Jikhaishi, and Sofio married Nestor Sanadze. Vasasi’s daughter was Tamar Kachakhidze, and Sofio’s daughter – my mother, Olga Sanadze.

This photo was made by Givi Todadze. He gave it to me about fifteen years ago when he learned that the “some woman” from Graneli’s poem—Tamar Kachakhidze—was my aunt.

Sadly, Vano Apridonidze passed away suddenly on May 8, 2022. I wasn’t able to conduct a full interview with him. Along with his vast knowledge and life experience, he took with him many unique, historical stories. These “comments” about Terenti’s muse are like a few rare pearls scattered from a much greater treasure.

I later contacted Mr. Vano’s sister, Mrs. Darejan Apridonidze, who now lives in Switzerland with her son. She wrote to me:

“Tamar had an archive, and we are still searching for it, but we haven’t found anything. Vano also looked for it, but without success. Vano knew so much -I didn’t. When Tamar returned from exile, I soon got married and moved to Central Asia, so I didn’t see her often. But Vano lived with her during his student years, so he knew a lot.

It’s true my aunt was later acquitted, and so was her husband, but it was a tragic time. Aunt never talked about those years, and no one dared to ask. Only Vano – he was the one she spoke to openly.

I remember one story: when she was arrested and sitting in a cell, Beria came and called her in Russian through the door, ‘How do you feel, Tamara Spiridonovna?’ – with full irony. My aunt raised her head and proudly replied, ‘Excellent, Lavrentiy Pavlovich. Excellent!”