Author: Mariam Mebuke

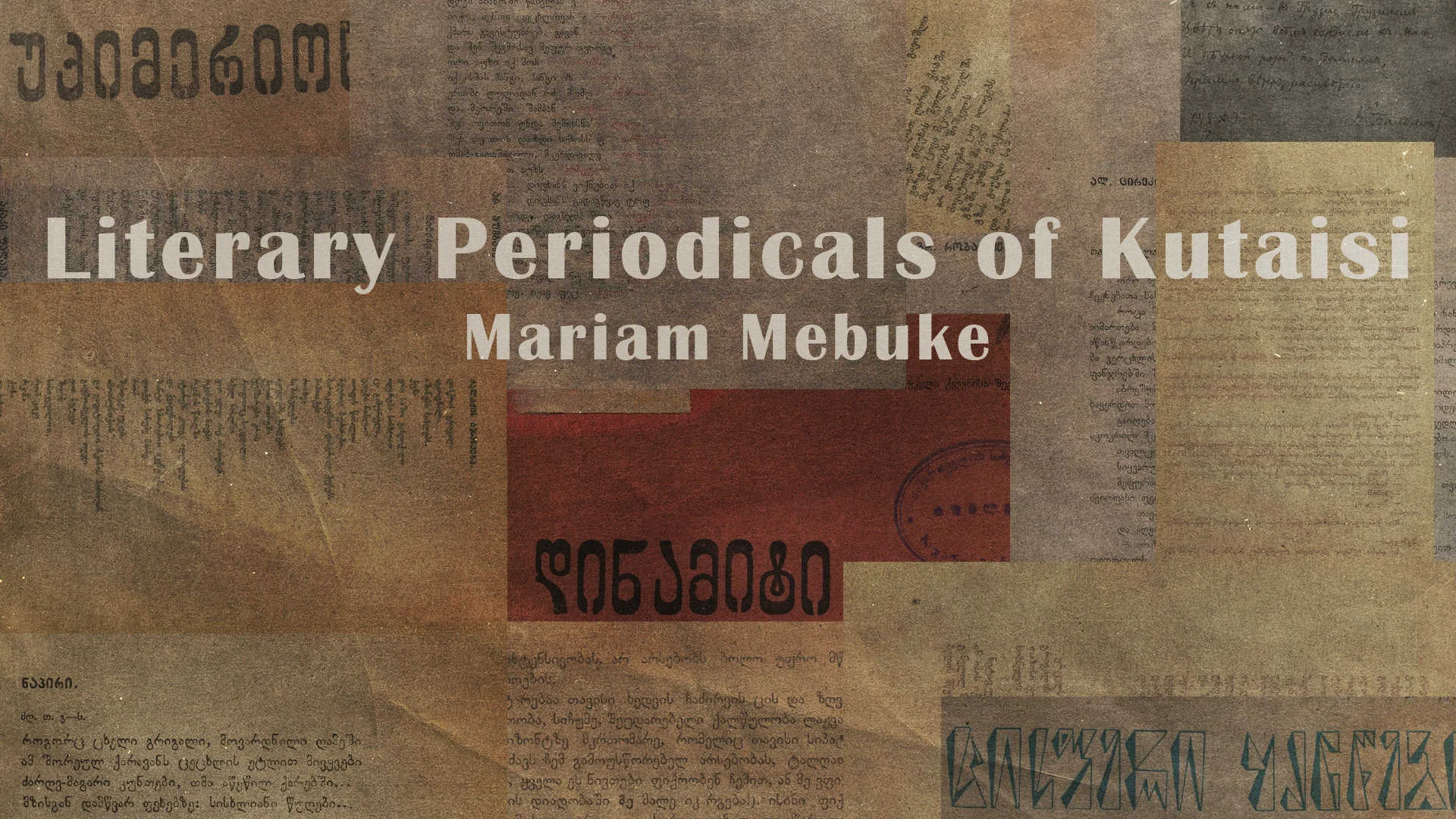

The creative legacy of Kutaisi in Georgian literature finds its roots with the first Georgian Symbolist poets and prose writers, who established a creative association and produced the magazine Tsisperi Kancebi (Blue Horns) in 1916, with only two issues published. This effort marked the beginning of a vibrant, if at times short-lived, period of literary expression, with various magazines and newspapers emerging over the years to document and influence the literary movements and creative energies of the time. Many such periodicals have since vanished, but a few notable ones still carry significant historical weight for their contributions to the era. As Avtandil Nikoleishvili aptly observes, these publications “served to revive the past literary processes of Kutaisi,” though much of their tangible legacy is elusive, as few records or copies have survived.

Following Blue Horns, the Kutaisi Artistic Writers’ Circle was founded and began publishing a newspaper called Armazi. Around this time, literary endeavors were consistently stifled by external forces. An issue of a literary almanac edited by Niko Lortkipanidze, as well as Khelovnebis Moambe, a monthly magazine planned but published only once, reflect the struggle against Soviet-imposed censorship, which often limited the life span of these periodicals. Unfortunately, little documentation remains on these publications, making it challenging to pinpoint the precise reasons behind their premature closures.

In 1922, another chapter began with the formation of the Kutaisi Writers’ Union, led by figures like Niko Lortkifanidze and Sandro Tsirekidze, one of the original members of Blue Horns. This organization aimed to periodically publish magazines, though they often saw only a single issue reach publication. Notably, the Kutaisi branch of the Writers’ Union was linked to the poet and translator Vaso Gorgadze, a native of Imereti. Gorgadze’s editorial work extended to his collection of poetry published with the assistance of Niko Lortkipanidze.

One of the most notable periodicals from this time was Ukimerioni, which launched in 1922 and produced six issues—a considerable feat given the challenges of the era. Some issues of Ukimerioni survive in digitized form. Its second issue includes Terenti Granelli’s poem Confession to Kutaisi and Davit Chkheidze’s (known by his pseudonym Dia Chianeli) essay, Kutaisi with Crazy People. In this piece, Chkheidze poignantly characterizes Kutaisi not merely as a city, but as a hub for creativity, highlighting the distinctive people who gave the city its character. The term “crazy,” used here to denote an artistic fervor rather than a derogatory label, captures the essence of an era when writers and poets sought to infuse their work with creative “madness,” even under the constraints of Sovietization.

In the “Artistic Chronicle” on the last page of the same issue, we find some ” news.” For instance, it mentions the Kutaisi branch of the Writers’ Union, where “the silent creative work of Kutaisi’s poets is being produced.” Here, “silent work” likely does not imply an attempt to evade censorship. This is because the Writers’ Union—like all unions during the Soviet period—was ultimately a conformist body, however overstated that might sound.

Ukimerioni often featured pieces on Symbolist and Futurist writers, prominent literary movements of the early 20th century. The Futurists, who gathered under the name H2SO4, held public poetry events, including notable performances by Vladimir Mayakovsky in both Kutaisi and Tbilisi. The “Artistic Chronicle” section of Ukimerioni documented cultural news, such as poetry readings and the illness of prominent writer Sandro Tsirekidze. Granelli, described as a “Poet from Tiflis,” was a frequent figure in these circles and was beloved by Kutaisi’s literary community even during challenging periods of his life.

The 1926 publication of Ushba, a fortnightly magazine that released six issues, contributed further to the city’s literary scene. The beloved Terenti Granelli collaborated with most of these magazines, a testament to his popularity among Kutaisi’s readers.

As the influence of proletarian writers grew, Soviet literary propaganda emerged through the press. While most of the previously mentioned periodicals had brief runs, Soviet Writer, a newspaper published by the Kutaisi Writers’ Union, lasted from 1932 to 1934. Similarly, publications like Words and Deeds and Dynamite conveyed Soviet ideology through literature. Dynamite contained works like In the Atmosphere of Work and Forge, embodying socialist realism and celebrating the October Revolution as a pivotal event for the transformation of society.

Though Kutaisi’s periodicals were often at the mercy of ideological control and censorship, these publications nonetheless fostered a distinct local literary culture. The Kutaisi Writers’ Union managed to survive through these difficult times, though its activities waned. Following a hiatus that lasted until 1975, the publication Gantiadi (originally titled Almanac) revived Kutaisi’s literary output. Founded by Guram Panjikidze and later edited by figures like Rezo Cheishvili and Konstantine Lortkipanidze, Gantiadi publishes poetry, prose, translations, and criticism, and remains in print to this day, with Temur Amkoladze serving as its current editor.

Despite the trials faced by Kutaisi’s literary community, the city’s periodicals managed to shape Georgian literary development and foster a unique creative space. Kutaisi’s enduring tradition of literary periodicals—beginning with the first creative circle of poets and writers—has demonstrated the resilience of literary culture, even under the shadow of censorship, and continues to contribute to the broader narrative of Georgian literature.