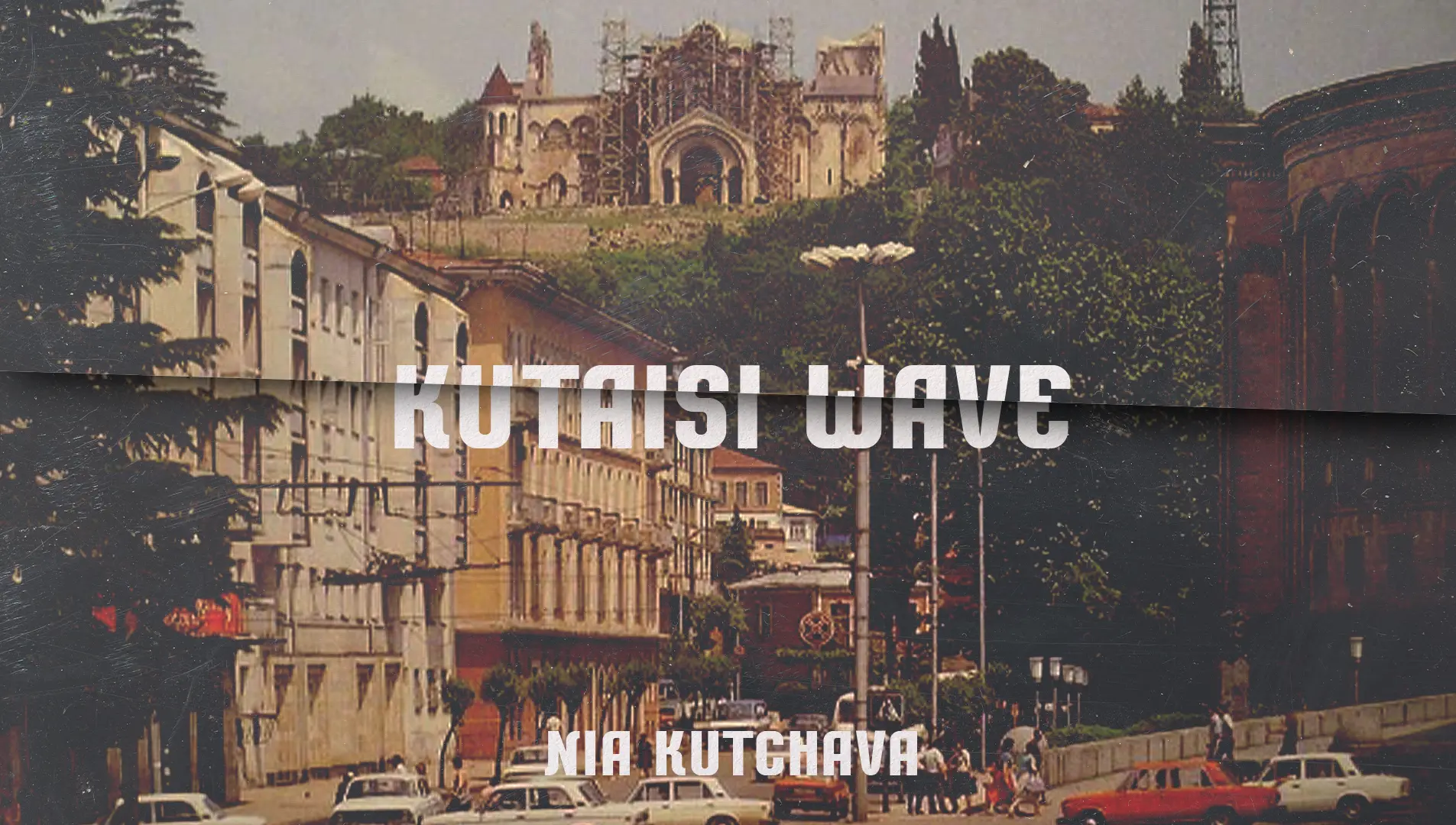

Author: Nia Kutchava

In the 1990s, a significant socio-political crisis erupted in independent Georgia, a period marked by a desperate search for identity in the post-Soviet era. This crisis involved dealing with deep social conflicts, rampant unemployment, and a high crime rate, making it a particularly tumultuous time for the country. The phenomenon known as the “Kutaisi Wave” emerged and evolved against this historical backdrop, representing a complex assessment of these turbulent times.

The “Kutaisi Wave” can be viewed as an expression of counterculture, which seeks to break away from established societal norms and values and free itself from the ideals adopted by previous generations. The proponents of this counterculture argued that traditional social practices were no longer effective and that it was crucial to push for change. However, defining the exact nature of the “Kutaisi wave” is challenging due to the difficulty in identifying a dominant culture during a decade characterized by crisis and significant political upheaval in Georgia.

Kutaisi, recently severed from the Soviet Union, had to find its place as a city in a new geopolitical reality. Understanding what preoccupied the residents of Kutaisi at the time reveals a collective identity that responded to feelings of disappointment and despair. The post-Soviet city, grappling with armed conflicts, civil strife, and political instability, formed a unique relationship with the capital, Tbilisi. Despite being marginalized from the main political actions taking place in Tbilisi, Kutaisi experienced a significant influx of non-governmental organizations aimed at monitoring local corruption, marking an early attempt to establish societal mechanisms independent of local political influence.

This isolation contributed to a cultural conflict, with a prevailing view in the collective memory of Kutaisi’s residents that the culture developed there tended to drain away to the capital, leaving the city in a state of cultural and political secondary importance. This situation was compounded by a stereotype of provincialism that has become a caricature in modern times.

Music played a pivotal role in articulating the protest inherent in the “Kutaisi Wave.” In Soviet politics, music was seen as a flexible tool for initiating and expressing protest, synthesizing melodies and lyrical content to reflect personal and collective anguish and the broader social resistance. During the 1970s in the Soviet Union, rock music, though distributed illegally and suppressed by the state, became a symbol of resistance against the oppressive regime.

The late 1980s and early 1990s saw punk music take root in Kutaisi, becoming a crucial form of expression among the youth. The city’s young people altered their appearances and adopted various clothing styles to signify their allegiance to different musical genres and the broader protest movement. These aesthetic choices solidified their identity within specific musical subcultures and symbolized their broader discontent and societal grief.

The most defining aspect of this movement was its use of symbols—clothing, hairstyles, and accessories—that expressed individual and collective dissent and acted as a physical manifestation of their resistance. This identity was so robust that it set them apart from mainstream societal values, which they saw as outdated and oppressive.

“The Outsider,” one of Georgia’s prominent bands, became synonymous with the Kutaisi wave. Their music and style, particularly evident in their song “It’s Dark in the City,” resonated with the global punk scene’s disdain for authority and apathy towards societal norms. Despite this, Robi Kukhianidze of “The Outsider” distanced the band from Western musical influences, citing pure Georgian music and the artistry of Hamlet Gonashvili as their true inspirations.

In addition to the protest and its cultural significance, it’s crucial to acknowledge that against the backdrop of a youth movement, the challenge to social norms often manifests through deviant actions. Deviance refers to behavior that diverges from society’s generally accepted values and standards. Such behavior can foster unhealthy thoughts and beliefs and can be criminal in nature. To comprehend deviance, we can draw on sociological concepts and theories that help identify the causes and consequences of such behavior.

Howard Becker’s “Labeling Theory” addresses the nature of socially unacceptable behavior. Becker portrayed deviance as a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy. He believed that members of a subculture transform the future negative perceptions and labels imposed by mainstream society into an outward expression of their individuality. This may serve as a form of protest, as subcultural members adopting stereotypes could demonstrate the absurdity of outdated and incorrect societal thinking. Over time, however, these stereotypes often evolve into self-fulfilling prophecies, as individuals expected by society to commit crimes end up doing so and thus conform to societal expectations.

Amid the Kutaisi wave of the 1990s, criminal activity and delinquency in the city significantly increased. It’s important to note that in Tbilisi, stereotypes about Kutaisi had already formed, linking the so-called Kutaisi wave music with the “black world” of crime and deviance. Another significant theoretical model relevant to understanding deviance during this period is Robert Merton’s “Strain Theory.” According to this theory, deviance and crime emerge when society lacks legitimate means for individuals to achieve their goals and acquire the necessary social capital. Social capital encompasses economic well-being, political power, and prestige, recognized and valued by society. Merton’s theory is particularly applicable to societies where state structures have crumbled amid transformative historical processes, making criminal behavior a seemingly effective strategy for attaining goals and gaining social capital and power. This reality was particularly pertinent to Kutaisi in the 1990s.

Today, Kutaisi is engaged in reevaluating outdated societal views and establishing new values better suited to modern realities. This ongoing transformation suggests a breaking away from older subcultures and a movement towards a unique and authentic cultural expression, rooted in the experiences and individualism of Kutaisi’s youth.