Author: Nia Kuchava

Dori Laub, a psychoanalyst and professor at Yale University, developed important insights while researching trauma and how it is shared, expressed, and listened to. According to him, when a person shares their inner pain—something not yet fully understood or expressed—with another person who truly listens, a unique and deeply emotional situation is created. What makes this experience so extraordinary is that the listener is not hearing a story already told in museums or recorded in archives. Instead, they witness something being born for the first time—pain that has never had a chance to be revealed before.

Historical facts and context are present, but they do not reduce the importance of the listener. Instead, they offer a backdrop. The act of sharing trauma allows the storyteller to give shape to emotions that go beyond everyday feelings—emotions that are often intense, elusive, and hard to define. In return, the listener confirms that the story is real and meaningful. Based on Laub’s ideas, I believe it is especially important to see and understand the stories of ordinary people during times of political repression and historical change. These personal experiences help us better understand the emotional and psychological truth behind historical events. Everyday memories filled with fear, sadness, and uncertainty allow us to see history through human eyes.

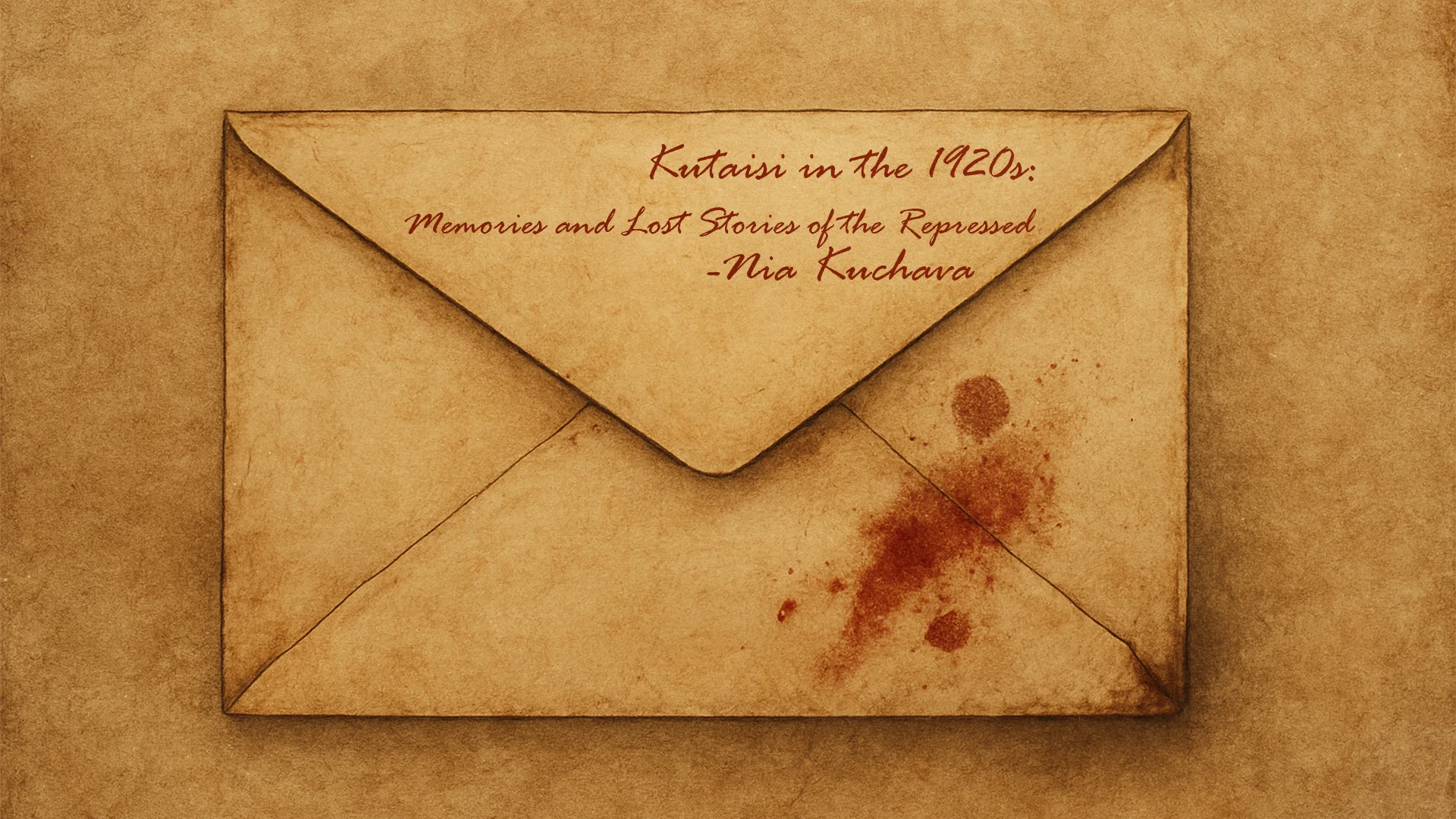

This is the kind of lens through which we should look at Kutaisi in the 1920s, by uncovering the repressed memories hidden in letters, notes, and personal stories—giving voice to people who were silenced and finding an audience that will listen and recognize their truth.

One powerful example of such a memory is found in the letters of Davit Sharashidze, a former member of Georgia’s Constituent Assembly. In 1921, after the fall of the Democratic Republic of Georgia and the start of Soviet rule, Sharashidze wrote letters to his fellow party members in Europe. These letters describe everyday life in Kutaisi and reflect the emotions of ordinary people—sadness, isolation, and internal struggle under the new regime.

In one of his letters, Sharashidze writes about Filipe Makharadze’s visit to Kutaisi in April 1921. Although many people came to see the parade, their silence during the communists’ speeches said more than words. As Sharashidze described, the quiet response showed that the Red Army and Bolshevik leaders had no real support or legitimacy in Georgian society. In fact, the people found subtle ways to express their true feelings. When the communists praised the Red Army, the only response from the crowd was: “Long live the Georgian army! Long live the heroes of Tabakhmela!” This was a symbolic act of resistance.

Makharadze later held a meeting to try and present an image of unity and obedience. A few people clapped when the communists criticized the previous government, but this reaction was forced. One notable voice during this meeting was Gogita Paghava, who boldly stated that the First Republic of Georgia was a government created by the will of the people and truly served their interests. He was allowed to speak thanks to the support of those present, and because Sasha Gegechkori, fearing criticism from the Mensheviks, agreed to let the people’s voice be heard. This memory clearly shows the gap between public silence and private beliefs, and how people resisted a regime that tried to control them.

Another story that reveals the emotional and political reality of the time is that of Minadora Orjonikidze-Toroshelidze, a member of the Constituent Assembly since 1919. She studied at the Kutaisi Women’s Gymnasium and later received a medical education in Geneva. Her interest in politics grew during this time. After the Soviet invasion, she became a victim of the regime twice—first in 1924, when she was exiled to Moscow for leading an underground women’s organization that supported families of prisoners, and again in 1936, when she was exiled to Central Asia.

Minadora was born in Ghoresha village, near Shorapani, and later moved to Kutaisi with her father and sister to continue her education. Her memories of arriving in Kutaisi with hope and curiosity show a more personal and human side of her, beyond her political identity. When she finished high school, she and her family traveled to Kutaisi by train, hoping to find places for the girls in local schools. Their tears and disappointment moved the teachers, who gave them hope that some spots might become available. This marked the beginning of Minadora’s connection with the city.

Her political journey began in 1898, when members of the “Mesame Dasi,” the first social-democratic group in the Caucasus, were sent to Kutaisi. She attended their meetings and joined their underground activities. In her memoirs, she recalls a conversation with actor Lado Meskhishvili, who believed theater was a powerful way to educate society and raise awareness.

In 1921, Minadora worked for the Red Cross while her husband was imprisoned in Kutaisi. She was offered a chance to go to Europe, but chose to stay in Georgia with her children, unable to leave her homeland. In one emotional moment, her relative Sergo Orjonikidze visited her. When he asked about her sadness, she replied, “I bury your dead!”—a bold and painful statement, according to her grandson’s account.

In 1937, during Stalin’s purges, her husband was labeled a member of a “fascist gang” in the newspaper Communist. Minadora was also accused of saying that the Bolsheviks had “massacred the workers” in 1924, and that Lenin had betrayed the Georgian people by supporting the Soviet invasion.

In her memoirs, Minadora writes that work was her only refuge. It helped her not to be alone with her memories, her pain, and her past. These stories, filled with trauma and endurance, deserve to be heard and remembered. Her testimony shows the suffering of a repressed Georgian woman and reminds us that trauma does not disappear when it becomes part of history—it continues to live in personal memory and must be shared to be fully understood.