Author: Manana Kurtsikidze

An extraordinary exhibition begins. Sapichkhia – David Kldiashvili, the Boulevard – the Ishkhneli sisters, the Theater Yard of Meskhiashvili – Lado Meskhiashvili and Kote Marjanishvili, the House of Writers – Lado Asatiani, “Zastava” – Vasily Kikvidze. The Pantheon of Outstanding Figures at Mtsvanekvavila – one, two, three…

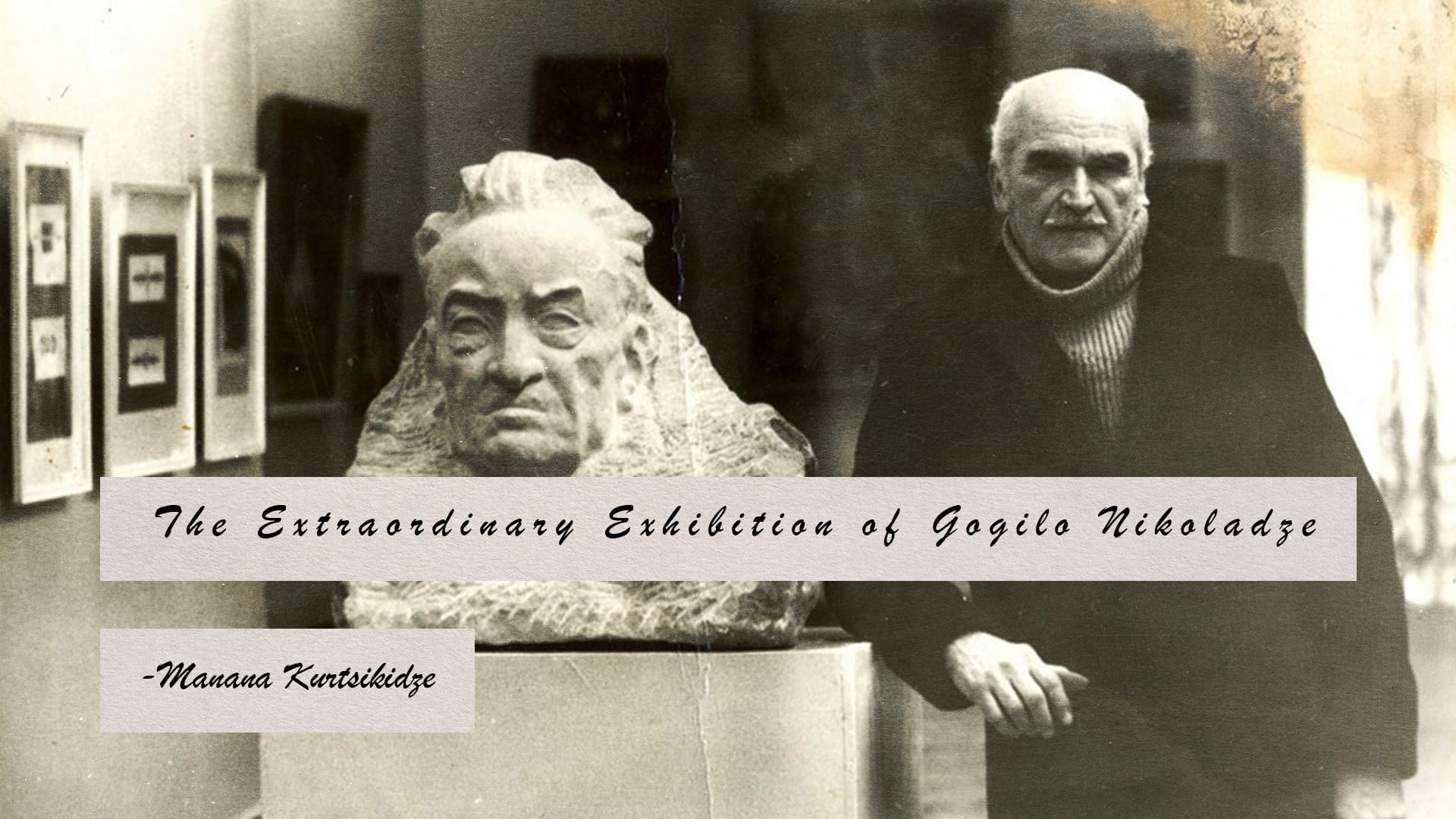

Do you remember the “extraordinary exhibition”… of the one who “brought half, if not the whole, city to life in stone,” Eristavi at the Kutaisi Cemetery – at his own personal exhibition? This is not just the “tragic fate” of one person but of all the sculptors in a small town. But in this case, Aguli has one prototype for whom the whole city is indeed an extraordinary exhibition. Gogilo (Giorgi) Nikoladze himself, after his son-in-law Rezo Gabriadze, immortalized him in the character of Aguli Eristavi, no longer belongs only to Kutaisi.

And again… the old and prestigious street of the old city. A house – covered in ivy, strangely attractive. In the yard, a large blue fir tree stands on the green grass. “Rooted” sculptures “grown” from the earth. Here lived the artist who called himself “the son of Jakob Nikoladze and the grandson of Rodin.”

So, let’s begin…

…………………………….

He closes his eyes and sees… just like in a movie… in a second, he is there, in the “Matsonashvili house” where he was born. He always remembers this house, perhaps more for its architectural perfection. Beautiful ornaments, winged cherubs. A thousand captivating figures that (as he believed) determined his future profession.

The first serious memory. Upper Imereti. The village of Itkhvisi. His grandfather was a village pastor, Deacon Iosif Tsereteli—Father of eight children. The house has a stone facade in the shape of a rhombus, on which he later (at his grandfather’s request) personally carved the construction date – 1886. These are the photographs in his memory. He vividly recalled the summer when, after a long delay, his grandfather, summoned to the “Kantora,” quietly opened the door and, lowering his head, entered the house, then his room, which also served as a chapel. His grandfather no longer had a beard. The Communists had shaved it and banned worship services. Gogilo, who sometimes combed his white-bearded grandfather’s beard, now did not even dare to enter that room. The old deacon did not leave it, sitting in contemplation and prayer.

…………………………………….

Mother – Anna Tsereteli, and father – Eusebius Nikoladze. A church singer, and a graduate of the Saint Petersburg Theological Academy. His mother, along with the Ishkhneli sisters, sang in the Georgian choir. A cultured and educated person. An art lover. Therefore, he always spoke of his mother’s merit in ensuring that his first passion and love – sculpture – became his profession. Anna was always ready to recognize her son’s talent. She encouraged him, and praised him, saying, “My son will be a future sculptor.” Gogilo also “selflessly” sculpted and carved out of stone everything that came his way. Thus, he touched immortality, and his first work became the dog Mimi, the inseparable friend of the little maestro.

…………………………………..

Seeing his attraction to drawing, a school teacher advised him to join an art studio. There he was taught by the legendary teacher Vano Cheishvili, the mentor of almost all Kutaisi artists and himself a graduate of the Imperial Society Art School in Petersburg, a pupil of Ilya Repin. A teacher – a miracle. He shared with the children not only the technical secrets of drawing but also the magic of art. His room was full of miniature copies of Michelangelo’s masterpieces, evoking an inexhaustible interest in future sculptors. …and the main secret to an artist’s success that he learned from him: “If you don’t like it, erase it and draw it again. Until you like it.” After this, he tirelessly and persistently did it – again, again, again.

Erase and start again. Erase and start again. This is the great test of the creator, and these words were repeated once more to the academy student by the fine sculptor Jakob Nikoladze.

………………………………………….

He studied. He made his first steps. He had his first attempts. The first goals were set. All these primary emotions… sound (gramophone) are accompanied by a sad melody… of war. In the art studio – shattered copies. The school – a hospital. Night shifts in Sapichkhia (a district in Kutaisi). Dimly lit rooms and falling asleep on a stone pedestal in the shape of a couch at the house of Shalva Eliava. Kutaisi Central Post Office. He himself worked there. In triangular letters, he brought tears and joy to the residents of the streets of Kirov, Gogebashvili, and Tskhakaia.

…………………………………………………………….

Tbilisi. 1942. War again. The days are gray, the nights black. All windows and openings are tightly boarded up. Gogilo Nikoladze is a student of the sculpture faculty of the Academy of Arts. The professors – famous artists and sculptors – Nikoladze, Kakabadze, Charlemagne, Kobuladze, Merabishvili, Mikatadze, Kandelaki.

The most important thing is… the exam.

The Great Jakob entered and asked: “Who here is Nikoladze?” He looked at the work, nodded, and left. They spared no one in the learning process. Coming to the academy early, he walked around the students. He would stop by Gogilo, and check his tools, his working instruments. If he didn’t like something, the verdict was: “Tear it down and start again!”… until he was satisfied.

…………………………………………………….

He studied, sculpted, worked.

At the statue factory… he “revived” damaged statues in Eastern Georgia. In the workshops of Merabishvili, Kakabadze, and Mikatadze, he tried his chisel. Here, too, he had to deal with the great leader. He almost sacrificed himself while caring for a six-meter-tall clay figure. He sent a telegram to Shota Mikatadze, who was in Leningrad, about a crack in the chest: “A crack has appeared in the area of the tunic.” The next day, he was taken to the police station. They confirmed that the content of the telegram was not the code for an encrypted message.

…………………………………

Kutaisi called him. The old father, now alone, called. (His mother died the year he entered the academy.) He thought it was the best decision. Ucha Japaridze contributed to his acceptance. He advised him to come to Kutaisi and help establish the artists’ union together with other artists. In his work, the Kutaisi epoch of immense labor began, in which no creative time-out can be found. It’s enough to list just the portraits, and you’ll see the scale of the physical and spiritual tension that accomplished his creative ascent. Petre Chabukiani, Kote Marjanishvili, Lado Meskhiashvili, Vasil Amashukeli, David Kldiashvili, Pavlika Tumanishvili, Nikolo Muskhelishvili, Valerian Mizandari, David Kvitsaridze, Lili Nutsubidze. Many more faces, familiar and unfamiliar.

Together with these faces, his creativity was written. Along with his beloved teacher and friend Valerian Mizandari and the inseparable Petia Bagrationi, against the backdrop of old Kutaisi humor, what he himself called “music” was created.

………………………………………….

Valerian Mizandari was a separate life for him. Separate creativity. Together and apart. But did they ever part after Gogilo came to Kutaisi? All the memories, all the creative successes, all the joys were together and shared. Together, they tamed the clay, breathed soul into the stone, and hunted, together they went to Ilo’s photo studio. They drank, they joked. They “cemented the foundation” of Kutaisi bohemia and color, and spontaneously, without knowing it, they created brief sketches of Rezo Gabriadze’s future scripts. Almost no memory, even the saddest, was without a smile… This smile was born of talented humor. We all know that all of this is close to each of us and that it belongs to us more than anything else. Valiko Mizandari, just this name became known to millions thanks to Rezo Gabriadze. I’m not even talking about Valerian Mizandari’s dog – Perry…

Sometimes their joint work led to creative conflicts. Sometimes Mizandari yielded to his friend, and Gogilo worked with both of them as co-authors.

Gogilo Nikoladze remembers Mizandari in many ways. In a state of creative frenzy. Relaxed, drunk. Stuck in true and false memories, like Münchhausen. There was much humor in him, work, and love for the society of his beloved city.

Then it was enough not to be afraid of life.

…………………………………….

He constantly searched for faces.

A pupil of the great portraitist Jakob Nikoladze, this was in his blood.

Jakob himself inherited from Rodin the constant search for types.

One day, he came across an interesting type. Fine features. A refined, intelligent face. Over the years, he worked as an “editor” in a small work booth under the stairs of the executive committee.

However, he became a legend in Georgian cinema. The first documentary filmmaker. Vasil Amashukeli.

Gogilo mustered the courage and asked him to pose for a bust. The first documentarian gladly accepted the prospect of coming to life in stone, and within a few days, sitting in a chair in the bright studio of the ivy-covered sculptor’s house, he recounted stories of filming Akakia’s journey to Racha-Lechkhumi.

The bust was well-received by the public. The exhibitions were successful.

For the second time, he himself came to the old and sick Vasil Amashukeli. On the Gora(a district in Kutaisi), near the Bagrati Temple.

The bronze bust by Gogilo Nikoladze adorns the director’s grave at Mtsvanekvavila (a district in Kutaisi). With the inscription “In Memory of Vaso Amashukeli. Sculptor Gogilo Nikoladze.”

………………………………………………

He sculpted Petre Chabukiani’s bust three times. He himself said that he held great love for this man. To show his simplicity, his humanity, and his respect for him. The old scientist loved his studio. He would knock on the door with his cane, instantly revealing his personality. Then he would sit and talk for hours about Sataplia. In a book given to the sculptor, he wrote: “To the esteemed Gogi Nikoladze, who honored me and presented me with an invaluable gift. Petre Chabukiani, 1966.”

……………………………………………………

He loved this portrait very much. He wanted to do it when he was in Spain. When he saw the Cervantes Memorial. He remembered the Georgian Cervantes – David Kldiashvili, the father of “autumnal nobility.” He always had a special connection to him. And when his bust was commissioned for an all-Union exhibition, the search began. Again, the search. Although he saw many photographs of the writer, he studied the face of almost every old man in the city. At the market, he came across the right type. He was trading in iron and steel. His facial features were very similar to the writer’s. He circled around him for a long time, but the grandson, who was next to the old man, got scared of this circling and immediately took his grandfather away from the market. It took a long time to find him again. One Sunday, he suddenly decided to say a familiar phrase, repeated a thousand times to others, now to him. The portrait was a great success. However, the David Kldiashvili that adorns his city today is another portrait. The bust of the Georgian Cervantes at the intersection of two streets emphasizes the eternal relevance of his stories, synthesizing the princely and “autumnal noble” images.

……………………………………….

He worked on the busts of Lado Meskhiashvili and Kote Marjanishvili for almost ten years. One on the right, the other on the left, adorn the majestic building of the Meskhiashvili Theater. He worked on both almost simultaneously. He didn’t like something, so he broke everything and did it again. The unveiling of both busts was pompous, with great celebrations and honored guests, as was known in the communist era. Gogilo Nikoladze unveiled the bust of Kote Marjanishvili together with Veriko Anjaparidze. Veriko touched his heart. For him, it was like a dream. The great Veriko and himself. In 1985, a year later, Meskhiashvili’s bust was also unveiled, and today both are part of Kutaisi. As if they had always stood there.

…………………………………………

The Kutaisi epoch and its “Purple” – a family member, a doctor, educated, beautiful, (only… not Dmitry Gelovani) – Nora Gabriadze. He had liked her for a long time. He watched from afar. There was something magical about this woman. Charisma. Charm. The “Purple Woman.” The sister of Rezo Gabriadze… His friends told him he would not dare approach her. He dared. He tamed. She became his life companion. Their family. With white statues, and white walls. With white, bright people… Guests, journalists, friends. Much humor. The heroes and characters of Gabriadze, the memories of writing each story, and Homeric laughter. Gogilo’s struggle with the statue was constantly accompanied by the theme of the sculptor’s illness – sciatica. The husband was almost always in Kutaisi. The wife is in Tbilisi with her son at work. But they wanted to grow old together, and they again settled together within the walls of the cozy and beautiful house.

…………………………………………..

Today they are no longer here.

Now it’s another time.

The artist’s house on Tbilisi Street is full of loneliness. The blue fir stands in the tall grass, and Shota Rustaveli has grown from the ground once more. The old ghosts still roam those places.

(An impressive sight – the venerable sculptor travels through the labyrinths of the human soul.)

Everything remains the same. He is in his coat. With his inseparable cap. Wandering under the old blue fir. He enters the now old studio. Slightly bent at the waist, but still an imposing man. He grumbles. He says he no longer feels as strong as before. He is about to create a portrait of his “father,” Jakob Nikoladze.