Author: Lia Kharaidze

In Chiatura Municipality, there is a small village of 180 households – Tskhrukveti. Although modest in size, it would be difficult to find another village that has given so many scholars to the homeland at the same time. It is here, in a picturesque setting, that a beautiful oda house – a type of traditional Georgian mansion – stands, bearing the name of Academician Giorgi Tsereteli for the past forty years.

In earlier times, the Tsereteli Palace stood on this very site, serving as a gathering place for the Georgian intellectual elite of the 19th and early 20th centuries: Akaki Tsereteli, Galaktion Tabidze, Niko Nikoladze, Ivane Varazashvili, Grigol Zdanovich, Konstantine Abashidze, and others. Although this historic residence was later destroyed, the building that now functions as the Giorgi Tsereteli House-Museum possesses an equally remarkable history of its own.

The house was purchased by the great Georgian patriot Mikhako Tsereteli. Mikhako Tsereteli was an active public figure and one of the founders of the university. His translation of the Epic of Gilgamesh was recognized as the best translation at the 2010 World Congress of the Ancient East held in Cambridge, United Kingdom. In 1933, he deciphered the Assyrian-Urartian bilingual inscription of Kelashin, earning him the title “Patriarch of Urartology.” His work Nation and Humanity is the first Georgian sociological study, and in general, Mikhako Tsereteli’s scholarly legacy has yet to be fully explored. Following the Soviet occupation of Georgia in 1921, he was forced into exile and is buried at the Leuville estate in France.

During the uprising of 1914, Giorgi Tsereteli was arrested. The demolition of his ancestral home coincided with this turbulent period. Upon his return from imprisonment, his uncle Mikhako Tsereteli, wishing to protect his nephew from despair, immediately purchased a wooden hut in a neighboring village and constructed a new house there.

Giorgi Tsereteli was born into the family of the prominent Georgian physician, publicist, and political figure Vasil Tsereteli. He belonged to the renowned Modzgvrishvili-Tsereteli family and was a direct descendant of King David II of Imereti. He graduated from the Faculty of Philology at Tbilisi State University. Immediately after completing his postgraduate studies, he was invited to serve as an associate professor of Arabic at the Leningrad Institute of Living Oriental Languages.

After returning to Georgia, he played a leading role in training scientific personnel in various fields of Semitology. He headed the Department of Near Eastern Languages at the Institute of Language, History, and Material Culture. He was awarded the degree of Doctor of Philology for his monograph Armazi Bilingualism, and in the same year received the academic title of Professor. On his initiative, the Faculty of Oriental Studies, the Department of Semitology, and the Institute of Oriental Studies at Tbilisi State University were founded.

As a linguist, Giorgi Tsereteli left behind an immense scholarly legacy that could be discussed at length. However, the focus of this article is the Palestine Expedition. The expedition, which included Akaki Shanidze, Irakli Abashidze, and Giorgi Tsereteli, proved to be extraordinarily fruitful. The emotionally charged Palestinian Diaries of poet Irakli Abashidze remain deeply moving to readers today. Several excerpts from these diaries deserve particular attention.

October 25

“We must begin work immediately, this very morning…

But so far, we know nothing about Israel. First, we stand on the roof of the Franciscan Catholic monastery, on its wide veranda, and gaze upon old and new Jerusalem.

Here is Golgotha…

Here is the Church of the Resurrection…

The Tomb of Christ…

The Tomb of Omar…

The high tower of Eleon… Zion…”

“We are late – at least a hundred years late,” Akaki Shanidze says sadly. It seems that this painful realization passes through all three of us at the same moment. “In general, it should be noted that in all monasteries founded by Georgians, the Greeks are destroying every trace of Georgian activity…”

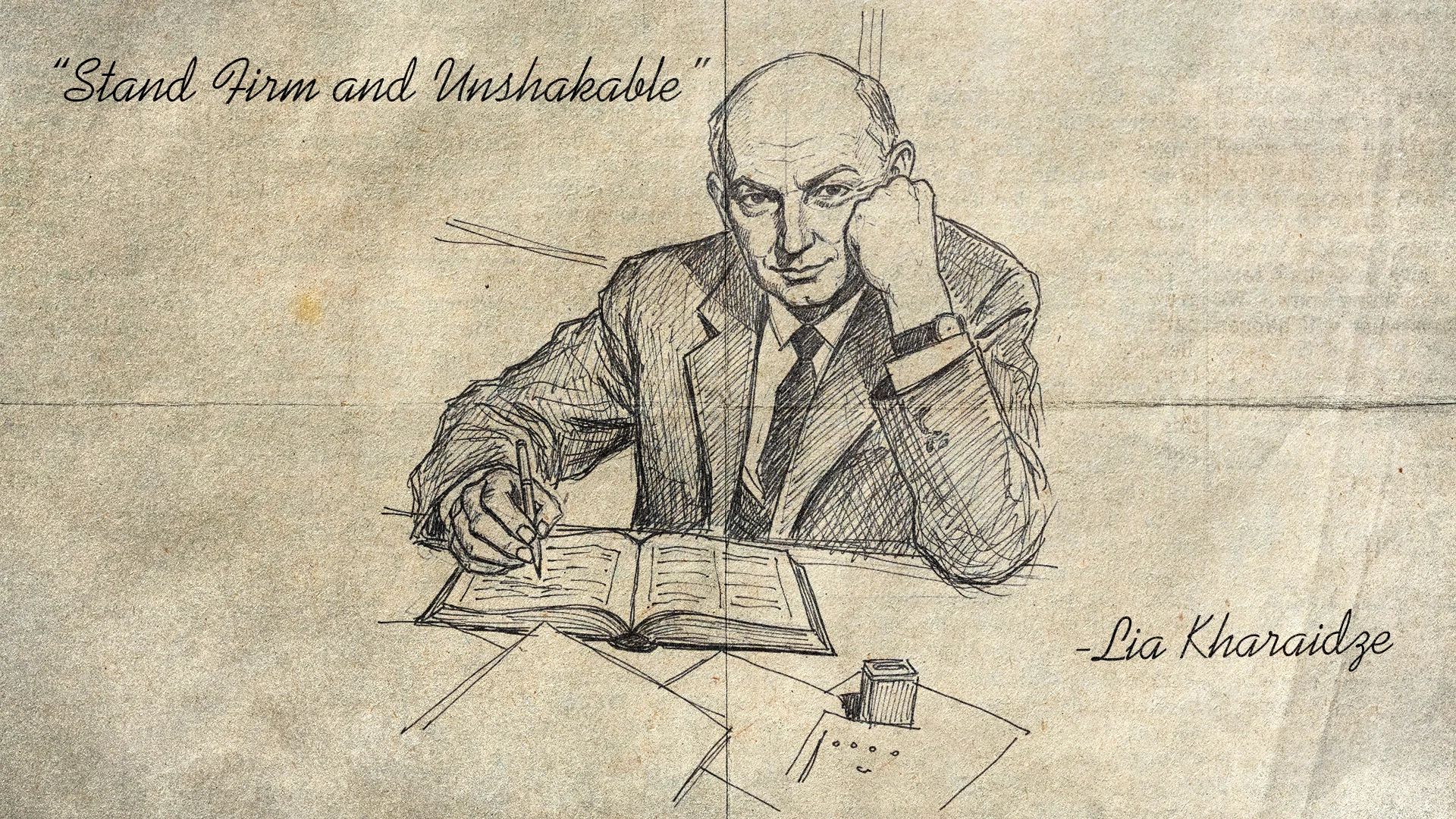

“And yet, here they are – traces of Georgian blood firmly embedded in the mosaic stones of the floor, appearing here and there like mist. From when? Whose?… In the center of this strange haze, I noticed a metal disk set into the floor, bearing an inscription in Georgian Asomtavruli script. I immediately called Akaki Shanidze and Giorgi Tsereteli, who were examining inscriptions and frescoes on the walls. Together we read: ‘Stand firm and unshakable.’ A shiver ran through me. This small metal disk seemed to lift me upward, as if the hum of the sacrificed or the cry of swordsmen had risen from beneath the floor, from somewhere beyond the centuries.”

The Georgian expedition encountered immense difficulties at Jvari Monastery. Georgian frescoes and inscriptions had been erased and covered with black paint. Fortunately, earlier descriptions provided scholars with sufficient evidence of the existence of Rustaveli’s fresco. Despite determined efforts to eliminate it entirely, the Georgian presence could not be erased from this remarkable monument of culture, nor from the sacred site that Georgian kings had protected for centuries.

“As soon as we entered, Academician Giorgi Tsereteli and I went directly to the right column. Where should the portrait of the great Shota be?… We stared intently when suddenly the scholar said quietly, with restrained excitement: ‘This is what was painted… This is what was painted – without doubt, this is it.’ Here is the inscription, the famous inscription – we have found it. I urged the scholars to decipher more words. It looks like fingers, the imprint of fingers. Here is an eye – a real eye… Akaki Shanidze notices it as well. There are fingers, there are eyes – we confirm unanimously. Even the Greek monk Dionysius confirms it. This is also a hat; this is also a second hand…”

Today, it is difficult to imagine that there was a time when we did not know of this extraordinary fresco, when we did not know the appearance of the great poet.

“Giorgi Tsereteli and I soaked a piece of canvas in water and carefully attempted to remove the black paint covering Rustaveli’s fresco. We took turns, anxious and cautious. As we approached the face, we warned one another, cleaning it gently, fearing even the slightest damage. It was a miracle – the colors were untouched. They emerged cleansed and radiant as before. Vasha! The majestic face of the wise old man appeared – proud, yet deeply sorrowful, astonishingly familiar.”

Today, photographs of Rustaveli’s fresco and of the Palestine Expedition, retrieved through such effort, gaze at us from the walls of the Giorgi Tsereteli Museum.

Another revealing episode is connected with the fresco. One day, as the Georgian scholars hurried to Jvari Monastery to continue their work, they encountered a Greek monk attempting to damage the image. They arrived just in time. Overcome by emotion, Giorgi Tsereteli struck the monk with his open hand. The incident escalated into a serious scandal, requiring diplomatic intervention to resolve it discreetly.

Giorgi Tsereteli deeply loved Imereti, and above all, his native village of Tskhrukveti. Academician Tamaz Gamkrelidze recalls that in the final years of his life, when Giorgi Tsereteli was gravely ill, he longed for the taste of water from his village spring. It was brought to him in a clay jug. To this day, the spring is known as “Tsereteli’s Water,” and anyone who has tasted it will understand the scholar’s final wish.