Author: Mariam Marjanishvili

Exactly a hundred years ago, in Kutaisi – one of Georgia’s oldest cities – a group of young symbolists was formed. They were given the unusual name “The Blue Horns.”

The color blue has long been an emblem of Romanticism and Symbolism. It first appeared in a dream of Novalis. The Romantics sought a mystical blue flower, as mysterious as the Holy Grail of medieval Christian knights. Later, the Symbolists adopted blue as the sign of a distant, boundless, and otherworldly world – the realm of spirits, which in everyday language also meant death. The symbol of happiness, the blue bird, was sought by the siblings Tiltil and Mytila in the famous play by Maurice Maeterlinck. Interestingly, this play was incorrectly translated into Russian as “The Blue Bird”.

The young Georgian poets connected this European symbol with local tradition. By adding “kantsebi” (horns) – an important attribute of Georgian heritage – they gave the “blue flower” a distinctly Georgian form. For them, the name also carried associations with love and bohemia.

“These dreamy young men sat on the steps of the Soboro, spent nights in poetry, organized Hoffmann evenings, played cards, drank wine, roamed the city noisily, and sometimes even behaved like hooligans. Some experimented with opium (Paolo Iashvili), others fought against epidemics (Sandro Tsirekidze, Shalva Karmeli).”

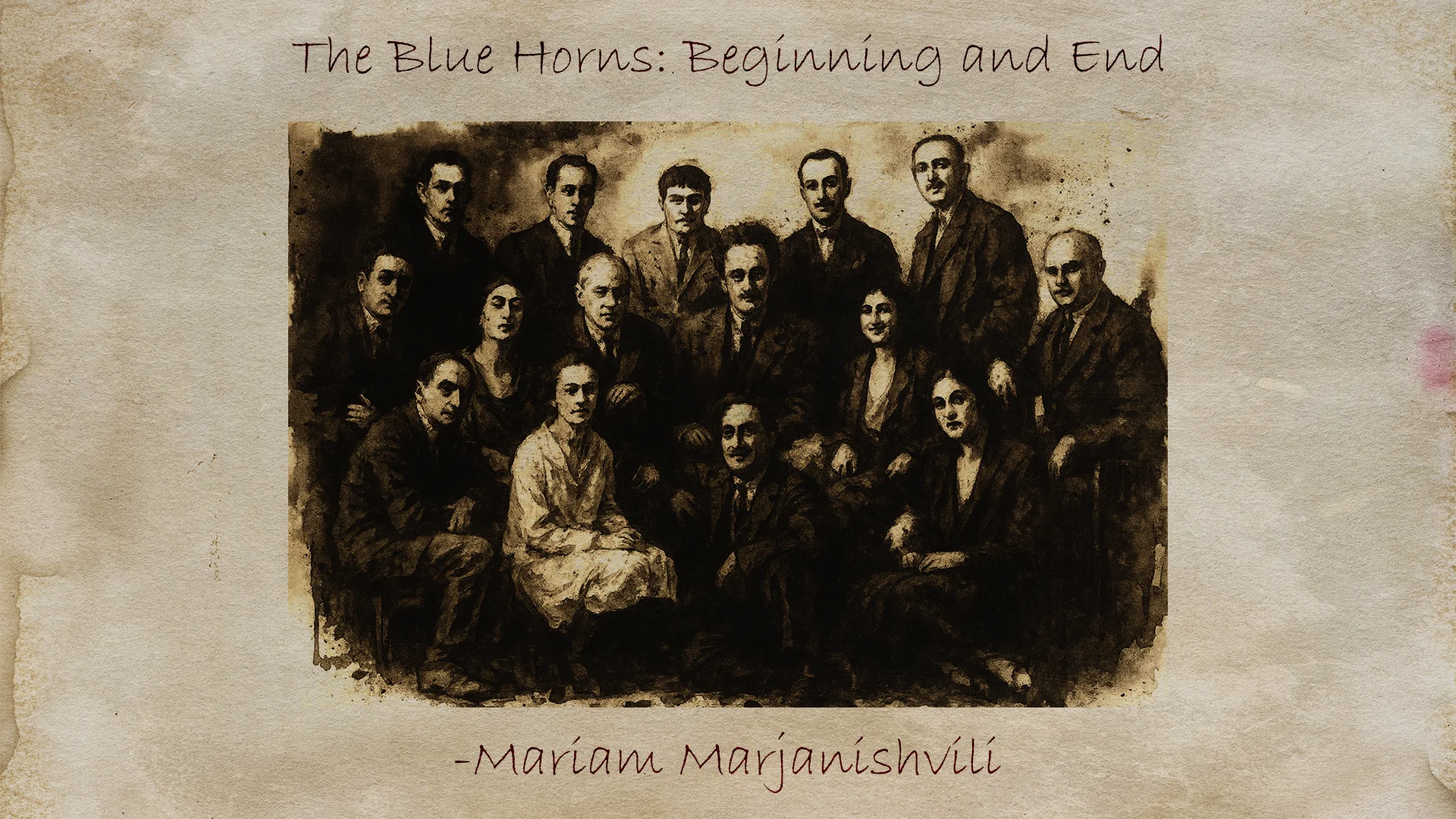

Among the “Blue Horns” were Grigol Robakidze, Paolo Iashvili, Titian Tabidze, Valerian Gaprindashvili, Kolau Nadiradze, Sandro Tsirekidze, Ali Arsenishvili, Giorgi Leonidze, Sergo Kldiashvili, Razhden Gvetadze, Shalva Apkhaidze, Nikolo Mitsishvili, Shalva Karmeli (Gogiashvili), Ivane Kipiani, and Leli Japaridze. All of them became true masters of language and revealed their talents through the “Blue Horns” school.

In 1916, the “Blue Horns” made Kutaisi so noisy that the echoes of their presence are still remembered today. Their sudden appearance created thousands of myths and legends. Society, however, often met them with suspicion and hostility.

A letter from Iason Bakradze to Giorgi Zdanovich on March 21, 1916, describes the mood:

“At the moment, they are talking of nothing else in Kutaisi but the ‘Blue Horns.’ Recently, at a lecture given by Kato Mikeladze about the situation of women, the second part was dedicated entirely to condemning the Horns. The theater was full, and she was rewarded with endless applause.”

Kato Mikeladze, Georgia’s first feminist, later continued her sharp criticism in the 1920s. She believed that in the world of the “Blue Horns,” a woman existed only as an object of male desire, either as a speechless matron or as a seductress.

The Horns, on the other hand, considered Kutaisi a city of jokers and gamblers who despised literature. Their opponents mockingly called them Futurists.

The main convener and editor of their first magazine was Paolo Iashvili, who tried to establish the spirit of pure art in provincial Kutaisi. He even wrote the manifesto “Tsinatkma”, and the members gave themselves Italianized names: Paolo (Pavle) Iashvili, Titian (Tite) Tabidze, Nicolo (Nikoloz) Mitsishvili.

Sandro Tsirekidze later wrote: “Paolo Iashvili is the bold architect of the Order. Like Atlantis, he holds the weight of the Blue Horns with both hands.”

Not everyone rejected them. Literary critic Kita Abashidze supported the group, defending their art during heated debates. Although he belonged to the 19th century in his aesthetics, he believed in evolution and saw symbolism as the next stage after realism. Because of this, he encouraged the youth.

Still, the outrage was strong. In another preserved letter to David Meskhi, the author ridiculed them:

“My dear, I saw Pavle Iashvili’s ‘Kantsebi’ in the Kutaisi Almanac. What a delusion! How can Kita not be ashamed to support this? Imagine, nothing hurt me more than hearing that Aristo Chumbadze is also involved. What a pity!”

Inside the group, members showed extraordinary solidarity. They resembled, as someone noted, “the thirteen Assyrian fathers who sowed Christianity in Kartli.” Unlike many literary circles, they had no internal conflicts.

They also gave each other symbolic roles: Robakidze was the “cardinal,” Paolo the “most holy,” Titian the “leader of poets,” Giorgi Leonidze the “flag,” and Nikolo Mitsishvili the “brain of Georgian poetry.”

The Horns helped establish Symbolism in Georgian literature. Titian Tabidze himself wrote: “Symbolism was introduced into us by Grigol Robakidze.”

Although Robakidze later denied his connection to the Horns, his influence was undeniable. Writers such as Galaktion Tabidze, Titian Tabidze, and Valerian Gaprindashvili created strong examples of symbolist poetry, which the Horns embraced. Galaktion’s “Me and the Night,” “Mary,” and “Blue Horses” were admired by the group, and Paolo Iashvili even read “Mary” from the stage.

All Georgian modernism at that time was moving toward Europe. Even politics reflected this spirit, with Prime Minister Noe Zhordania declaring: “I prefer the imperialists of the West to the fanatics of the East.”

In 1921, the “Blue Horns” became part of the “New Membership Union,” declaring that their focus was purely aesthetic and not political. Unfortunately, they welcomed the arrival of the Bolsheviks, mistakenly believing that political revolution would also bring artistic renewal. This illusion was soon destroyed by the brutal repressions of 1924.

The brotherhood also suffered from betrayal and loss. When Grigol Robakidze emigrated, his former friends turned against him. A pamphlet criticizing him was published under their signatures, and even the artist Lado Gudiashvili mocked him in caricatures. In 1935, Robakidze was expelled from the Writers’ Union and stripped of Soviet citizenship.

If their days in Kutaisi began with alcohol, bohemian aestheticism, opium, and the search for truth in darkness, their end in Tbilisi came with despair and death.

As Titian Tabidze wrote:

“We will stand on the Mukhrani Bridge to drown; life in Georgia is suicide.”

Nikolo Mitsishvili echoed this tragedy:

“All my cells suddenly failed me, and my blood was poisoned by extinction.”

The “Blue Horns” remain the only truly pure literary association in Georgian literature. Their goal was not politics or personal gain, but the search for new art. Each member achieved this individually, yet together they created one of the most important movements in Georgian cultural history.