Author: Lia Kharaidze

The discovery of manganese ore in Chiatura in the 19th century had a major impact on the development of the Imereti region. It gave a strong push to the creation of new transport links and the growth of industrial sectors in Georgia. The rapid development of production naturally led to the rise of an industrial culture.

The importance of industrial heritage is widely recognized internationally. Its study, preservation, adaptation, and conservation are a priority in the cultural and research activities of many countries. Georgia has a rich cultural heritage, which has been studied in many directions. However, the country’s industrial heritage still remains outside the focus of professional research. Architectural and engineering buildings and structures built for industrial purposes in the 19th and 20th centuries are often undervalued and not studied systematically.

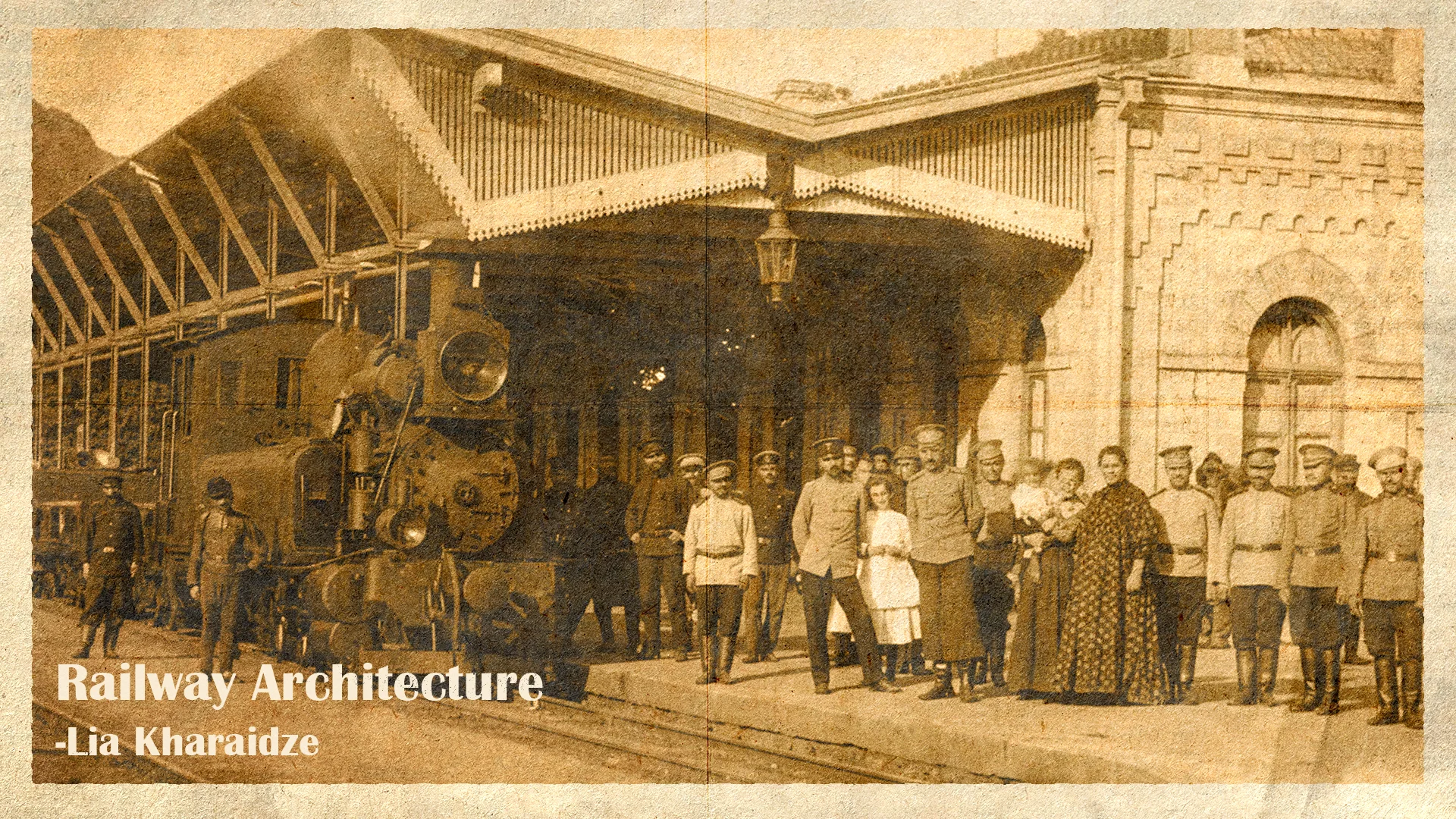

This article focuses on three important monuments of industrial culture: the Shorapani, Chiatura, and Sachkhere railway stations. It is worth noting that Shorapani station was granted the status of a cultural heritage monument in 2015, highlighting its historical and architectural value.

The Georgian Railway has a long and interesting history. From its founding until today, it has played a key role, as it represents the shortest route connecting Eurasia between the Black and Caspian Seas with Europe and Central Asia.

Construction of the railway in Georgia began in 1865 during the Russian Empire. One of the most difficult issues was the transportation and export of manganese ore, which directly affected the cost and competitiveness of Chiatura ore in international markets. At first, the ore was transported to Chiatura, then to the main station in Kvirila (now Zestaponi), and finally shipped abroad from the ports of Poti and Batumi.

Transporting ore by carts and horses on the poor roads of the Chiatura and Kvirila gorges was expensive and difficult. In fact, the cost of transportation was higher than the cost of mining itself, which raised the price of exported products. By the end of the 1880s, competition in the world market made the construction of a railway line even more urgent.

In 1885, the governor-general of the Caucasus, Dondukov-Korsakov, visited Princess Elena Tsereteli in Sachkhere. The head of the Transcaucasian Railway, engineer V. Presnyakov, accompanied him. Niko Nikoladze used this moment to push forward the idea of building the Chiatura – Shorapani railway line.

After returning from Sachkhere, Dondukov-Korsakov held a meeting with several important officials, including the head of the Caucasus Mining Department, V. Meller, the military governor of Kutaisi, General Snekalov, and the railway board. Presnyakov supported the construction of the line, but most officials, especially Meller, believed that the Chiatura deposit was not promising and advised against investing money.

Despite these objections, thanks to the tireless efforts of Giorgi Tsereteli and Niko Nikoladze, Emperor Alexander III approved the construction of the railway in 1891. A narrow-gauge railway line was built from Shorapani (in the village of Daba) to Chiatura.

The Shorapani railway station, one of the first station buildings in Transcaucasia, was put into operation in 1893. In May 1894, both the Chiatura and Shorapani stations were consecrated by protoiereus David Gambashidze.

The station is located in the gorge of the Kvirila and Dzirula rivers. Between 1846 and 1930, Shorapani was the district center, which included today’s Sachkhere, Zestaponi, and Kharagauli municipalities.

The one-story station building, constructed at the end of the 19th century, is decorated with symmetrically arranged arched openings around the entire perimeter. Its architecture belongs to the pseudo-Russian style, common in the Russian Empire at that time. One of the rooms still preserves its original design, with an ornamented wooden partition and a wall fireplace. Later remodeling changed some parts of the interior, but the floor covering has survived.

Nearby, a residential area was built for railway employees. These two-story houses, constructed in the same period, follow a common artistic style but differ in their decorative details. In 1909, a school was also built, adding to the ensemble. The architect is unknown, but the two-story brick building, decorated with fine details, still attracts admiration.

Shorapani itself is historically significant. It was inhabited in ancient times and known as “Sarapani” in Colchis. The fortress-city functioned as a port on the Kvirila River, serving as a warehouse for trade goods. According to Strabo (1st century BC – 1st century AD), ships sailed up the Phasis River to the Sarapani fortress, which was large enough to house the city’s population. Later, according to Vakhushti Bagrationi, it became the center of the Argveti principality in the 8th century. In the late feudal period, it developed into a small trading town. Leonti Mroveli (11th century) mentions that King Parnavaz I of Kartli built the fortress in the 3rd century BC. Today, the ruins remain, offering a clear view of the island formed by the confluence of the Kvirila and Dzirula rivers.

The Chiatura–Shorapani railway line was officially opened on February 4, 1895, though it had already been in use earlier. By 1906, the construction of the Chiatura–Sachkhere section was completed.

The Sachkhere railway station was built in 1904, when Princess Elizabeth Tsereteli successfully pushed for the extension of the line. The building, located in the city center on the right bank of the Kvirila River, was originally constructed of well-cut stone. It had a rectangular shape, with two floors on the sides and one in the center. Its decorations were simple but elegant, with carved cornices and arched window frames. The gabled roof was covered with tin.

Unfortunately, the building was destroyed in an earthquake, but was restored in its original form in 2000.

Princess Elizabeth Tsereteli, born in 1857 into the noble Tsulukidze family of Racha, was one of the most influential women of her time. She married Alexander Tsereteli but became a widow early in life. Despite her hardships, she dedicated herself to many social and cultural projects.

Her name is linked with the first library-reading room, a club, a theatrical society in Sachkhere, a hospital, a wooden bridge over the Kvirila River, and, of course, the construction of the railway station. She was the goddaughter of Tsar Nicholas II, which gave her influence in Russian circles. It was largely thanks to her determination that the railway line was extended to Sachkhere.

The Sachkhere station, opened in 1904, became a monument not only of industrial culture but also of her tireless efforts. Her daughter, Sonya Tsereteli-Avalishvili, recalled how many talented people she supported, even helping the young poet Galaktion Tabidze with a generous gift.

Sadly, her life ended tragically. After the Sovietization of Georgia, her property was confiscated. She lived in poverty in a damp basement in Tbilisi until her death in 1942 at the age of 85. She was buried in Vera Cemetery.

The Shorapani, Chiatura, and Sachkhere railway stations are not only part of Georgia’s industrial heritage but also significant monuments of its historical, cultural, and economic development. Their preservation and study are essential to ensure that these unique examples of industrial culture are passed on to future generations.