Author: Mariam Mebuke

Even though I’ve spent years living in Kutaisi, I still come across interesting facts and stories about places I’ve passed by many times and wondered about. This probably happens because I wasn’t born in Kutaisi in the 20th century.

At the start of this article, I’d like to point out one thing – I’m mainly trying to catch the attention of readers my age, those born in the 21st century, who know Georgia’s past mostly from stories told by others.

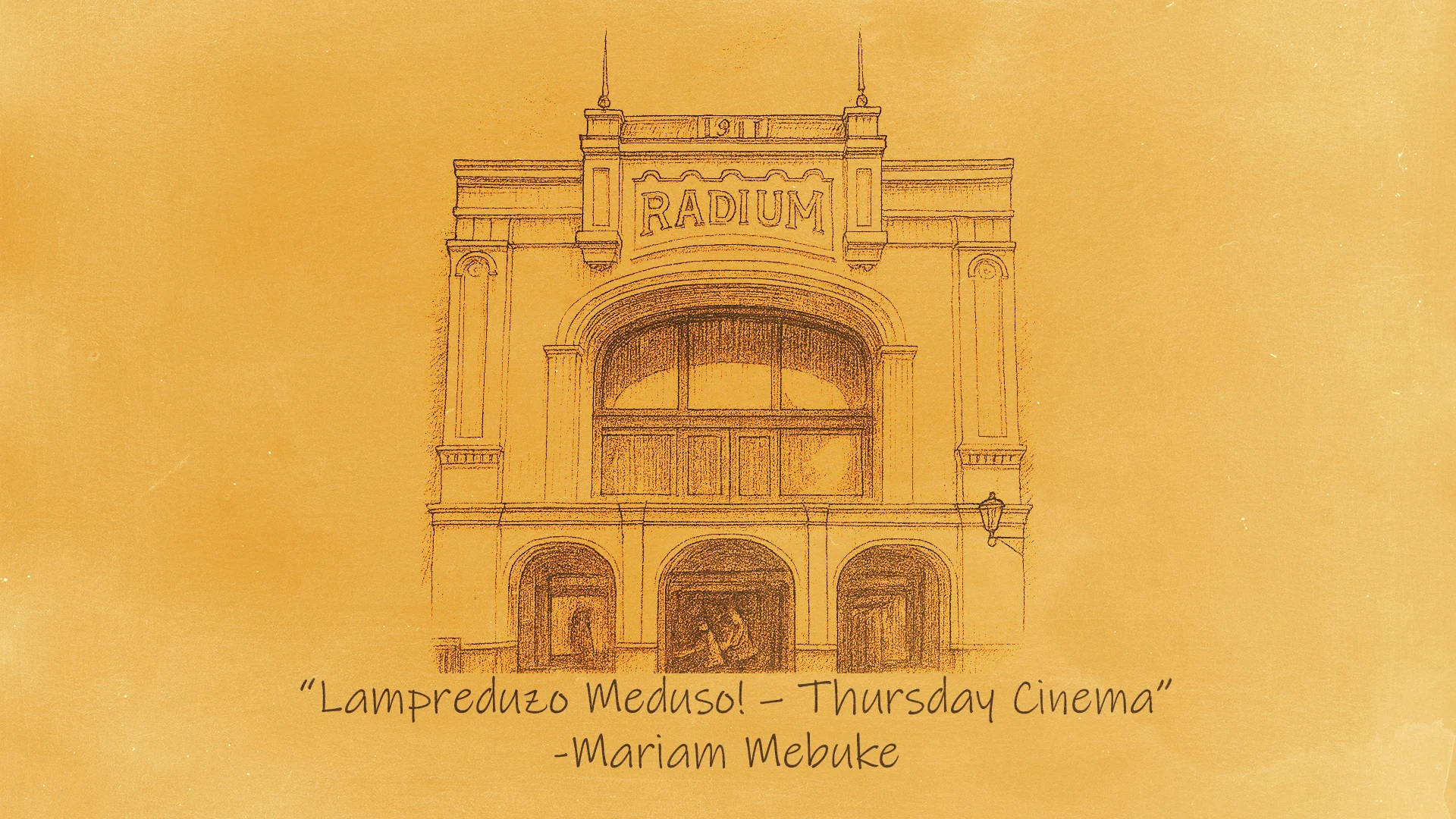

The word “Radium” is likely familiar to everyone as the name of a chemical element. But for those who have ever walked along Tsisperkantseli Street in Kutaisi and glanced – even for a moment – at the building in front of the First School, the word carries a different meaning.

The original cinema building once belonged to the Otskhele brothers, whose home was located next to the current Opera and Ballet Theatre. In 1911, after a fire, an Italian named Paulini bought the building on today’s Tsisperkantseli Street, which had already become a historical site. He wanted to reopen a cinema there and made several renovations himself. He built an 80-seat hall, but soon decided to return to Italy. Paulini then offered the building to Tikhon Asatiani and Pavle Mepisashvili in exchange for a certain sum of money.

Both Asatiani and Mepisashvili were members of the Kutaisi branch of the Society for the Spreading of Literacy among Georgians. Since they lacked the necessary funds, they turned to the Kutaisi Mutual Trust Society Bank for a loan, a type of local financial institution that also existed in Tbilisi and Batumi at the time, playing a vital role in supporting local projects.

In his memoirs, Asatiani wrote:

“…but I had no money. Nor could I find anyone to help me.

Finally, I turned to the Kutaisi Mutual Trust Society Bank, which gave me a loan to start the business. That’s how I acquired Paulini’s property.

I invited my childhood friend, Pavle Mepisashvili, to be my partner.

We began working, and in October of that same year, we opened a cinema that we named Radium.”

Later, Asatiani and Mepisashvili became the key financial and technical supporters of Vasil Amashukeli, the cameraman who filmed Akaki Tsereteli’s journey to Racha-Lechkhumi, capturing it with high artistic quality. The premiere took place in 1912 at the Radium cinema, and Akaki himself attended the screening.

This event became a significant memory for the people of Kutaisi – numerous historical sources and archive materials confirm its importance.

It seems that the cinema owners also used their profits for charitable purposes. One record, found on the website of Ilia State University, states:

“According to the November 28, 1912, issue of Imereti newspaper, Tikhon Asatiani and Pavle Mepisashvili donated 40 rubles to support the widow and children of Efrosine Bobokhidze.”

Clearly, this cinema had more than just an entertainment or educational function. Thanks to the goodwill of its founders, despite their limited resources, it also served a humanitarian purpose. A full discussion of their activity would go far beyond this article, but it’s important to at least mention their contributions.

From a 1911 Georgian newspaper:

“Very soon, the Radium Electrotheatre will open on Karvasli Street, directly across from the Boys’ Gymnasium. The hall will seat 400. The balcony boxes will have their own foyer, and the theatre will be heated in winter and have ventilation.”

At that time, opening a cinema in the city was a major cultural development. According to memoirs, early public lectures and events, such as the first meeting of the People’s University board and talks by prominent figures like Simon Kvariani and Dimitri Uznadze, were held in this cinema.

It’s also fascinating to see what kinds of films the early 20th-century audiences watched there:

“The Swedish Gymnastics School in Stockholm,”

“The Miserable Sick Man” (a comedy),

“Cardinal Richelieu and the Wife of the Duke of Chervez” (a historical picture), and many more – both feature films and documentaries.

Film screenings were accompanied by an orchestra, which was unusual for that time, when silent films were typically paired only with piano music.

The Radium cinema continued into the Soviet period, though of course it no longer looked or functioned the same. Cultural life in Georgia was deeply influenced by Soviet ideology, as we’ve discussed many times. This whole story reminded me of Lado Kotetishvili’s tale “Gochmana,” which captures the new rhythm and way of life in Georgia after the rise of communism.

During the Soviet era, the Radium cinema became a “Commune” theatre for the children of the second half of the 20th century. Morning movie sessions were organized for schoolchildren, and this is where the phrase “Thursday Cinema” comes from – well-known to generations of Kutaisi residents.

I plan to continue this story with more about Vasil Amashukeli, a native of Kutaisi who began making short films in 1908, such as “Types of the Baku Market”, “Daffodils”, and others, and later directed Georgia’s first full-length documentary. In fact, it’s believed that Akaki’s Journey might not only be the first Georgian feature-length documentary, but also the first in the world.

Cinema began developing rapidly in Georgia in the 1960s and reached its peak in the 1980s. Older generations often recall that attending film premieres was considered a must. Watching a new release at the cinema was one of the few forms of public entertainment and a kind of social tradition.

This golden age of cinema also brought new venues. In 1982, the “Suliko” cinema was built in Kutaisi specifically for movie screenings. Sadly, it only lasted five years, and no photos of the old building seem to exist in the archives.

In the early 20th century, the first cinema in Kutaisi was “Tamari”, which later became the Officers’ Club. Then came “Monplaisir”, later renamed “Damkvreli”. Even today, the old archway in the city center still carries the inscription “MON-PLAISIR.”

In the 1950s, the “Gamargveba” cinema appeared (its name likely linked to Soviet propaganda). By the late 1950s, a cinema named “Kutaisi” opened, and in 1978, the cinema “Sakartvelo” screened the premiere of the feature film “Data Tutashkhia.” Another venue, “26 Commissioners,” operated in the same building that now houses the Mask Theater.

The large number of cinemas speaks volumes about life in Kutaisi at the time – clearly, where there are many cinemas, there are many moviegoers.

Before finishing, I’d like to remind film lovers of the writers whose screenplays shaped Georgian cinema classics like:

“An Extraordinary Exhibition,”

“The Eccentrics,”

“Serenade,”

“Feola,”

“Don’t grieve.”

“Blue Mountains, or an Unbelievable Story”-

Rezo Gabriadze and Rezo Cheishvili, famously known as “The Two Rezos of Kutaisi.”

When I first visited Zakaria Paliashvili’s house-museum, I clearly remembered one thing: just outside his home flows the Rioni River, and on the very stones by the riverbank, the famous washerwomen scene from “Melodies of the Vera District” was filmed.

Kutaisi has a way of bringing old memories to life – not just those related to Georgian cinema, but to Georgian culture as a whole.

Even the great Italian director Federico Fellini once said about Georgian cinema:

“Georgian cinema is a unique phenomenon – a philosophical event, complex and yet innocent like a child. It contains everything that moves me to tears – and it’s not easy to make me cry.”

Indeed, the city of white stones continues to inspire.