Author: Sofiko Kanchaveli

This city has a soul – aristocratic and somehow majestic. It has color:

a mixture of plants and sunlight. It has strict geometry, both curved and twisted.

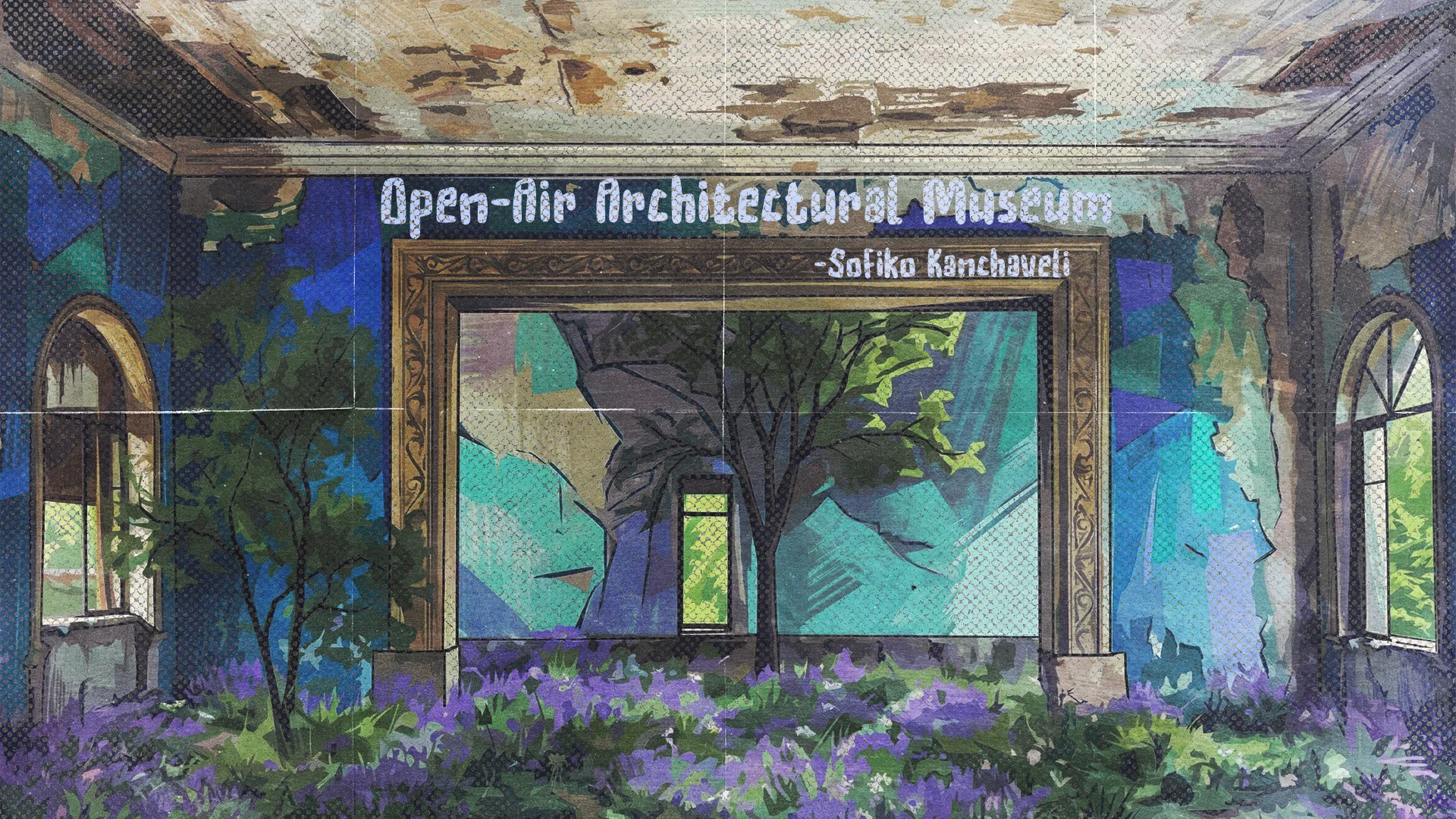

In the 1950s of the last century, sanatoriums built for the recreational function of the city, officially designated as a resort, appear today as conceptually significant architectural masterpieces representing different stylistic trends. Just a few years ago, the city – an origin of form, light, and the rebirth of nature – inspired actor Jim Carrey to purchase a moving NFT artwork created by Swedish artists Ryan Koopmans and Alice Wexsell. The work depicts a room in an abandoned sanatorium in Tskaltubo and is digitally processed as if the forces of nature had prevailed over the abandoned building.

You have probably guessed it – this is Tskaltubo, a resort town where, within a relatively small area, we can observe the development path of Soviet architecture. It is, in fact, an open-air architectural museum with its own unique planning and concept. Despite numerous damages, alterations, and near physical destruction, Tskaltubo has preserved its integrity and authenticity. Here, urban planning and architecture tell their story clearly and convincingly – about what was once the most popular resort.

After all, the main value here is the story, not any single object.

Art historian Tamar Amashukeli writes in her work “On the Urban-Architectural Value of Tskaltubo Sanatoriums”: during the Soviet period, the development of Tskaltubo and the construction of sanatoriums began in the 1920s and continued until the final stage of the Soviet Union. The healing properties of radon waters made the resort extremely popular, which was reflected in the growing number of visitors. During this period, new sanatoriums were built, existing ones were reconstructed, new wings were added, and relatively small sanatoriums built before the 1930s were replaced by new, large-scale complexes (Sanatoriums “Belgium”, “Samgurali”, “Rioni”).

In Tskaltubo, during the Soviet period, 21 sanatoriums and 9 bathhouses were built. Their architecture accurately reflects the architectural styles dominant in the Soviet Union and, consequently, in Georgia at specific historical periods.

Tskaltubo Architectural Styles

Constructivism (1920–1930) – a style in art, including architecture, which influenced global architectural trends and spread to Georgia with certain adaptations. A new architecture emerged, based on pure, basic forms and aimed at expressing an ideal and rational concept of realism. It almost entirely rejected decoration and, through the combination of geometric forms, sought to create functionally conceived architecture free from unnecessary details. This avant-garde style largely defined architectural trends of the 20th century.

In Georgia, both before and during the spread of Constructivism, it was important to study and integrate national architectural traditions. As a result, avant-garde principles were often mixed with elements of Georgian architecture. There are several interesting examples of Constructivism in Tskaltubo. Notably, all of them were built after the official ban on the style in 1932. The artificial and forced change of style was difficult, and this process continued throughout the 1930s, manifesting itself in various forms in buildings constructed in Tskaltubo during this period.

Examples include: Sanatorium “Tskaltubo” (1936) by M. Buzogli (father), L. Giorgadze (1967–1971); “Megobroba” (1937–1939) by S. Lentovsky, M. Kalashnikov (1951–1954); Sanatorium No.1 (the so-called Branch) (1939) by I. Kolchin.

“The sanatorium ‘Megobroba’, which is now in a deplorable condition, is a valuable and significant object not only because of its architectural qualities. As mentioned earlier, the change in style led to the ‘decoration’ of constructivist buildings with a ‘socialist’ façade across the Soviet Union. The sanatorium ‘Megobroba’ is a living example of the influence of politics on architecture. In the USSR, stylistic change was not merely a matter of taste or aesthetics -it was primarily dictated by political and ideological agendas. The sanatorium ‘Megobroba’ best tells the story of an era and a state in which not only people, but also architectural styles were repressed.” – Tamar Amashukeli.

Post-Constructivism – a transitional phase between Constructivism and Stalinist architecture, which lasted approximately 6 – 8 years and produced several noteworthy buildings.

Example: the Tskaltubo branch of the Scientific Research Institute of Balneology and Physiotherapy of the Ministry of Health of the Georgian SSR.

“The external appearance of the façades is largely determined by the interplay of volumes of different heights placed on different planes, creating dynamics through the alternation of vertical and horizontal directions. The building is moderately decorated with elements such as rustication, pilasters, orders, and cornices; however, the geometric clarity characteristic of Constructivism remains clearly visible.” – Tamar Amashukeli.

Socialist Classicism (Stalinist Empire style) – a style that largely shaped the appearance of Soviet cities, especially industrial and resort settlements.

“In 1932, an aggressive campaign was launched against Constructivism, accusing it of promoting ‘misunderstood austerity’, emotional coldness, ideological emptiness, and nakedness. The choice was once again made in favor of familiar classical architecture, which returned to the forefront after having been previously condemned. From the early 1930s, architects were instructed to master classical heritage. Priority was given not to one specific style, but to an ‘ideal’ mix of styles – visually familiar, yet new in content. The most important shift of this period was the move from functional and constructive issues to the ideological and symbolic meaning of architecture. Soviet architecture was expected to speak about the beautiful and happy life of the proletariat.

Was life beautiful? No. Therefore, a clear goal was defined – to replace reality with fiction. Culture was assigned a central role in achieving this goal. What should Soviet architecture be like? First of all, ‘beautiful’, pompous, monumental, luxurious, cheerful – in short, ‘like bourgeois palaces’. Classical architecture was prioritized, but enriched with national elements.” – Tamar Amashukeli.

Examples include numerous sanatoriums built between the 1940s and 1980s, such as “Tskaltubo”, “Rkinigzeli”, “Imereti”, “Medea”, “Gelati”, “Geologist”, “Aia”, “Georgia”, “Samgurali”, and others, each reflecting different phases of Socialist Classicism and later Soviet modernism.

Soviet Modernism, also known as pseudo-modernism, became a widespread architectural style throughout the Soviet Union and is today the subject of renewed interest. In most cases, Tskaltubo sanatoriums are located away from the central ring road, positioned at elevated points within spacious courtyards. Along the ring road surrounding the central park, the entrances to sanatoriums are marked by decorative gates and monumental staircases. Depending on the size of the territory – often two hectares or more – the path from the entrance to the main building is relatively long, allowing the visitor to approach the structure gradually. The view unfolds slowly, creating a distinct dramaturgy of perception.

For photographers, bloggers, wedding couples, anniversaries, and tourists, the sanatoriums have become especially attractive. Art critic Tamar Amashukeli writes about the sanatorium “Medea”: “The main value of the sanatorium lies in the 140-meter-long main façade, visually divided into two sections. One is a relatively short, rectilinear part with strongly projecting risalits on the sides and an even more pronounced central projection. On the second floor, the space between the risalits is designed as an arched gallery. This section largely defines the pompous yet light and airy character of the building.

The second, longer and more monumental section repeats the risalit motif, which unifies both parts of the façade. The wall plane is articulated by rectangular and arched openings, most of which are balconies. Their shapes are mainly rectangular and slightly arched, with rounded balconies placed within the large arches of the risalits. Between the risalits, on the second and third floors, raised zones framed by giant Corinthian columns are rhythmically arranged and recessed into the wall plane. Decorative elements are primarily borrowed from classical architecture, while national motifs appear in the paired columns of the first-floor gallery-porch of the longer section.”

And yet, Tskaltubo, beyond its role as an architectural museum, also embodies inspiration and the spirit of the muses, healing the soul along with the body. For some, it is a remnant of the past; for others, it is a city of architectural masterpieces. Locals unconditionally love green, quiet, beautiful, and pompous Tskaltubo. They are connected to the city through their own lives, and its stories are created by people who are both hosts and guests.

Tskaltubo evokes a feeling of awe and guilt at the same time. This remnant of glory does not belong only to the past – it is a beautiful structure of love for life itself, whose very name, meaning “current,” carries the expectation of new life.